Christian Education: God's Pedagogy (Part 1)

More than a decade before I had any formal educational aspirations, I remember reading Daniel 1:17 and marveling at what I perceived to be a rubric for the way God teaches. While I had little formal language (and even less formal training) at the time to put into words my intuition, the passage stuck with me over the years, becoming more important as my desire to pursue the calling and vocation of teaching grew.

Finally, after five years of seminary training in theology and education, my instincts found support biblically and pedagogically. What I had known instinctively I now began to understand pedagogically: as God did with Daniel, so we must also begin with the student in mind.

1) “And as for these four youth…”

We’ve already discussed to a degree who Daniel and his companions were as people, but who were they as products of their dual cultures (Israelite and Babylonian)? Any consideration of education has to begin with the consideration of those we may be trying to educate. Who are our students as people and as products of their culture(s) – familial, church, community, national? Where are they in terms of historical and cultural contexts – geographical, economical, political, technological? And when are they – mentally, emotionally, physically, socially, spiritually – with regard to developmental theory and their own growth?[1] Questions like these have to be asked and answered to only begin to understand those we teach.

In the school context, the entire process of getting to know my students begins with learning their names, asking questions (both formally and informally) about their lives, and learning family backgrounds and education history. It’s connecting with other teachers who may have taught them in the past as to what they said or believed at the time. It’s meeting and talking with their support systems – parents, pastors, and counselors – about the issues and ideas that are unresolved. It’s identifying peer group associations and keeping loose track of whom they hang out with, for upper schoolers – as are all of us – are defined by our communities and what they believe.

In addition to the personal exegetical work, cultural exegesis with regard to the social environments in which students live and have grown up is crucial to understanding them. Familiarizing ourselves with media referents and memorable touchstones of their lives is key to earning their trust, not to mention understanding shifts across and within their generation. Entering into their spheres of existence – especially the digital one – in a natural way is an important avenue for learning about those we hope to teach.

2) “…God gave them…”

The second aspect of God’s educational pedagogy that we see in Daniel 1:17 has to do with the Teacher and the Teacher’s character[2] – one that is expressly initiating and generous. As previously discussed in Daniel 1:4, God has already been at work in the lives of Daniel and his friends, gifting them with the basic capacities they will need to handle the capabilities He will later develop in them.

This generous initiation, of course, has much to do with God and both His omniscience and sovereignty. While we possess neither of these two qualities, we as parents and teachers have been gifted with the capacity and capability to model God’s initiation and generosity with our students in other ways, namely by actively seeking to know them and generously granting them access to get to know us as well. Though we are not God, we have the ability and the authority as their parents and teachers to initiate and generously provide the structure, support, and challenge they need to learn about themselves and us…but we must make the first (and often risky) move.

Whether at home or in the classroom, this involves sharing our own stories – the successes and failures – rather than defaulting to more generic and nameless examples to illustrate key points and ideas. It’s bringing our own creativity in the form of an original song or poem, taking a risk by putting it out there for those we parent and teach to consider, evaluate, and (gulp) pass judgment on, all while resisting the temptation to endlessly qualify or defend our attempts at doing so. It’s letting our students see our heart for them not only as their parents and teachers, but also as friends and fans. Granted, this potentially compromises a degree of authority in the adult-child relationship, but the risk is worth taking because of what it may yield in true respect.

[1] See “Life Span Development” by Ellery Pullman, pages 63-72; “Moral Development Through Christian Education” by James Riley Estep Jr. and Alvin W. Kuest, pages 73-82; “Faith Development” by Dennis Dirks, pages 83-90; and “Spiritual Formation: Nurturing Spiritual Vitality” by Nick Taylor, pages 91-98 in Christian Education, edited by Michael J. Anthony. Also, see “Patterns of Growth: The Structural Dimension,” pages 65-83; and “Patterns of Growth: The Functional Dimension,” pages 84-99 in Teaching for Reconciliation by Ronald T. Habermas.

[2] See “God for Us: The Trinity and Teaching,” pages 15-36; “God With Us: Jesus, the Master Teacher,” pages 59-86; and “God in Us: The Holy Spirit and Teaching,” pages 87-112 in God Our Teacher by Robert W. Pazmino.

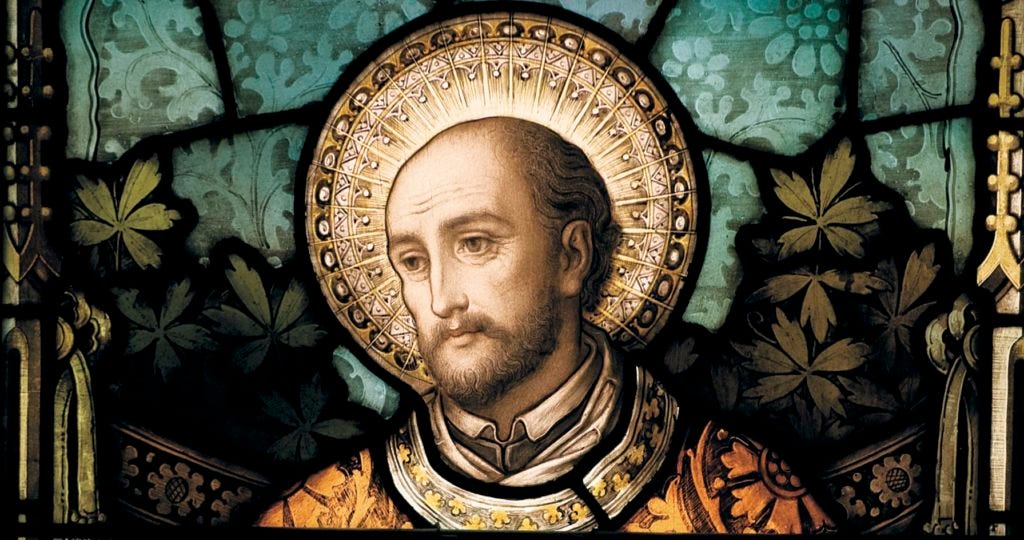

Stained glass: Ignatius, author of The Ratio Studiorum, the original set of guidelines for those directing Jesuit educational institutions in Europe.