Dear Reader,

When was the last time you shared, forwarded, or told someone about Second Drafts? Here’s a story (complete with accompanying business idea) from a reader helping the cause:

“Recently I flew out of the Bozeman airport and was proudly wearing my extra comfortable Second Drafts T-shirt. :-) As I was boarding the plane, the flight attendant read my shirt and said, ‘Oh, is that a brewery in Bozeman?’ Frankly the guy was very happy about the thought of a brewery called Second Drafts. I let him down gently that it wasn't a brewery, but it's the blog of a friend and he should check it out.

That got me thinking about your next business edit...a brewery called Second Drafts. Why? Because Life is a Series of Edits. Why not? Sounds like a great place for people to congregate, enjoy one another, and who knows, you might even do a philosophical, theological, Christian take on it. I’ve never been to a Christian-themed bar with a thoughtful bartender behind the counter. Might be a first. Reminds me of the TV show Cheers. Could be quite the place with the crowd you would attract, especially in Bozeman!”

I really appreciated this reader’s promotional efforts! Over the past 15 months, Second Drafts has stayed steady at about 300 free and 50 paid subscribers, but the open email rate, which averaged 50% in 2021, now averages between 60-65% in 2022, which by newsletter standards is tremendous (though still a ways from my goal of a regular 80% open rate). Apart from my own social media and the occasional T-shirt sighting in the airport, I don’t do any other promotion of the newsletter, so thanks for spreading the word. Every little bit helps!

Let me know your suggestions—even ones like a newsletter-themed bar!—that you think may expand readership and improve the experience. As always, thanks for reading Second Drafts.

Craig

PS: This week’s newsletter is a long one and Gmail clips emails at 102K, so you may need to continue reading it in your browser (see the end of this email for details on how to do that).

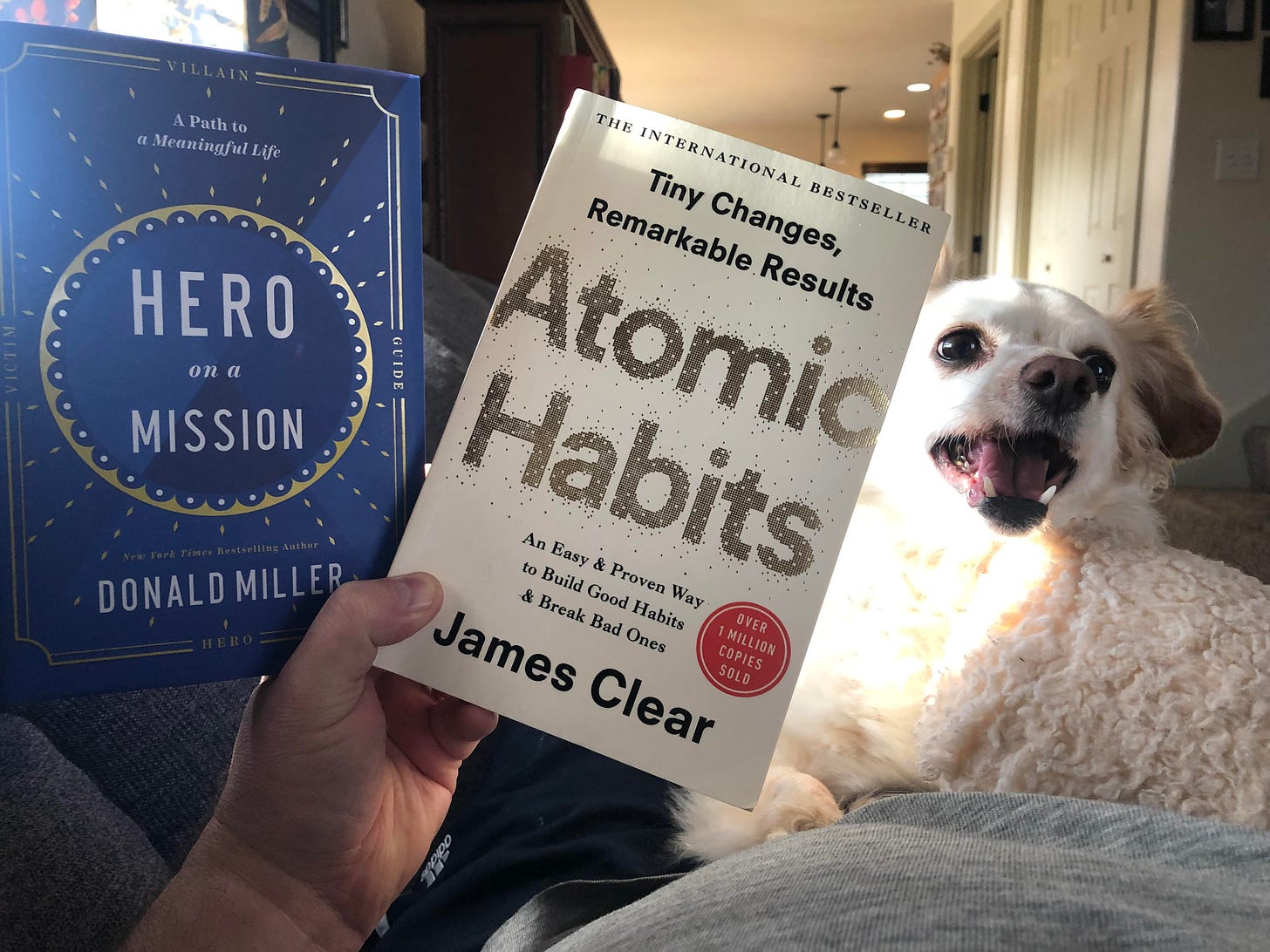

Programming Note: Peaches Picks Tomorrow

Paid subscribers, look for April’s monthly book review this Saturday (probably a little later in the day than my normal 5 a.m.—Peaches thinks I need my beauty sleep). Since we replaced the March book review with an extra podcast, this month’s review will be a self-help “twofer,” covering and combining James Clear’s book, Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones, with Donald Miller’s latest title, Hero on a Mission: A Path to a Meaningful Life.

Want in on the action? $5/month gets you access to all book reviews and podcasts.

Hot Takes

“58 Percent of Voters Open to Backing Independent Candidate If Faced with Biden, Trump: Poll” - As a guy who’s registered as an Independent, I can tell you that it can feel pretty lonely when it comes to finding a place to land in politics, particularly those of the Presidential variety. The good news is more people feel the same way:

“Fifty-eight percent of voters said they were open to supporting a moderate, independent presidential candidate in a contest between President Biden and former President Trump, according to a new Harvard CAPS-Harris Poll survey released exclusively to The Hill on Monday. Additionally, the survey found that majorities of voters said they do not want Biden or Trump to run in 2024.”

That’s the good news, at least from my perspective. Unfortunately, here’s the problem:

“However, among their own bases, Trump and Biden are the top 2024 presidential picks. Thirty-seven percent of voters said that if the Democratic presidential primary for the 2024 election were held today they would vote for Biden, while 58 percent said they would vote for Trump if the GOP presidential primary were held today.”

But this sentiment is not held just by us older independent voters; apparently, the youth vote has something to say as well:

“A research poll out of Harvard held several stark warnings for politicians—the youngest voting bloc in the country isn’t the least bit impressed with either party’s messaging and they intend to vote about it.”

Well, voting is good, but it’s only as good as the candidates for whom we get to vote. Can someone please figure out a viable third-party option/platform by 2024? Please?

“Celebrities Threaten to Leave Twitter After Elon Musk Takeover” - Two years ago, I read Ashlee Vance’s book, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, a title that, according to the New York Times Book Review, “will likely serve as the definitive account of a man whom so far we’ve seen mostly through caricature.”

I enjoyed the book, but I’m not sure anything has really changed regarding the aforementioned caricatured view of Elon Musk. In fact, based on what I’ve read all week, very little has. According to New York Magazine,

“It’s all pretty straightforward, according to the new management. In a statement announcing his $44 billion deal to purchase Twitter, pending owner Elon Musk wrote in a statement that the company’s core policies would remain the same: ‘Free speech is the bedrock of a functioning democracy, and Twitter is the digital town square where matters vital to the future of humanity are debated.’

But in direct messages and town hall comments on Monday, the people who make Twitter tick were more concerned with debating the future of their employment—concerned that the world’s richest man would not have their best interests in mind. ‘I feel like im going to throw up,’ one staffer told the New York Times in a direct message. ‘I rly don’t wanna work for a company that is owned by Elon Musk.’ One employee tweeted that they were ‘in need of a stiff drink,’ while another reportedly complained of Musk supporters inside the company: ‘Elon fan boys are braindead mouth breathers and we have a bunch of them at Twitter for the record. Can’t wait [until] he lays half of us off.’”

Caricature, of course, cuts both ways, and whereas haters have seemingly lost their minds over Musk surely being Satan, those who are fans have painted him as their new Savior before he’s even taken the reins and actually done anything. For a Twitter user like me, who is neither a hater nor a fan boy, it’s all cheap entertainment full of hysteria and hypocrisy on both sides. I concur with this reader, who wrote to say:

“I too have been enjoying the Musk thing. I hope he doesn’t have to waste $45B. Some people will try to sour things for him internally and externally. I guess if anybody can get through the drama, he can with his money and resources. Ultimately, I wonder if Musk will bring a better world and can he be trusted? While I think the guy is a current day genius, and I very much appreciate him, I just wonder. He seems to have integrity and conviction for worthy things and hobbies like SpaceX (although I see no value in Mars). I’m just concerned about all the building blocks he has. He really has the means to bring some (probably not so helpful) things to life.”

Perhaps, but that hasn’t been the modus operandi animating his business directions (though some say that’s not as true of his decisions concerning personnel and critics).

For me as a Twitter user, if Musk can deliver on his promise to level the platform’s playing field, I’ll be happy. But while I want to believe Musk is different from his Big Tech contemporaries at Facebook, Google, et. al., I continue to agree with Dr. Anthony Esolen that social media in general—because of its ubiquitous presence in our lives and human nature being what it is—should be managed and regulated as a public utility.

“The large Tech companies—Google, Facebook, PayPal, and so forth—have now become the equivalent of public utilities, like the phone company. That is just a plain fact. Therefore they must be regulated, as the phone company is. The details of such regulation must be hashed out by the people's representatives, because otherwise we will have ceded our civil liberties to the oversight of private and faceless citizens and their hidden algorithms and their unaccountable judgments and decisions.

I don't like Jabba the State, and on the face of it, it appears that I would be setting one Jabba against another Jabba, and hoping that you can restrain the one without growing the other. But I don't think that the analogy holds. That is because they are not really opponents. To restrain the power of Big Tech, in our current condition, is also simultaneously to restrain the reach and the power of government overseers of free speech. The growth of Big Tech has gone happily along with the growth of the Management State, and the withering of both the protective and the legislative power of the US Congress. After all, what is Congress but a few hundred people with their staffers? They do not play the role of David against the bureaucratic Goliath. They play the role of Goliath's flunky.”

For now (and in the absence of such utility regulation and the seemingly out-of-the-blue creation of the Disinformation Governance Board, the title of which sounds an awful lot like Orwell’s “Ministry of Truth”), I’m willing to see what Elon does—especially if before making any changes, he pulls back the curtain on the bias and censorship affecting the Twitter platform. But I don’t think Elon (or any other person) is Satan or Savior here, so let’s stop trying to make him into one or the other.

“Disposable Masks Could Be Used to Improve Concrete” - It looks like scientists have finally found an actual use (as opposed to preventing Covid-19) for those ubiquitous disposable blue masks:

“With the pervasive single-use masks during the pandemic now presenting an environmental problem, researchers have demonstrated the idea of incorporating old masks into a cement mixture to create stronger, more durable concrete.

In a paper published in the journal, Materials Letters, a Washington State University research team showed that the mixture using mask materials was 47% stronger than commonly used cement after a month of curing.”

As a friend (who is a surgeon) wrote, “An added benefit is that our roads will be stronger, cheaper, and will prevent spread of COVID via droplet transmission.”

Science!

Claiming the Right to Be Unhappy

My youngest daughter, Millie, is set to graduate from high school in June, after which she plans to work the summer in Bozeman (now taking employment offers!) before attending Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia, to study English with an emphasis in Literature and Writing this fall. The college very much wants her to attend, and has provided generous scholarship money to that end, for which we’re very grateful.

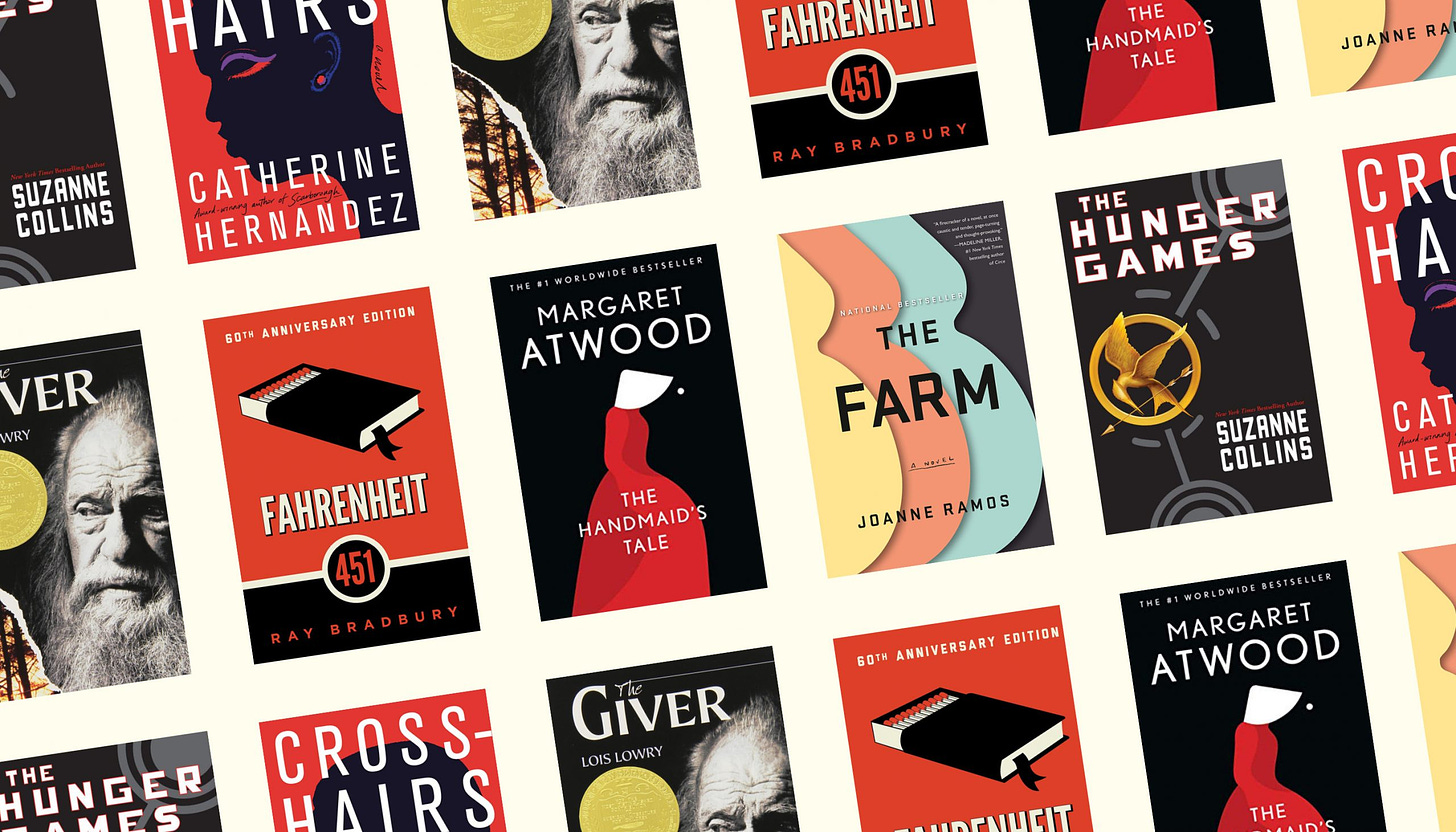

Earlier this week, Millie (along with the rest of her classmates), presented her senior thesis titled, “Claiming the Right to Be Unhappy: Reading Dystopian Fiction Through the Lens of Gospel Truth.” In her 20-minute presentation and 30-minute defense, she made the claim that the genre is “one that reinforces the beauty of what God has made in this world.” Only slightly biased, I think she makes a compelling case.

For readers with children or grandchildren who desire to enter those oft-dark literary worlds with your progeny, I share Millie’s unedited words to help you and yours find and walk in light.

“‘..All the tonic effects of murdering Desdemona and being murdered by Othello, without any of the inconveniences’ [The Controller said].

‘But I like the inconveniences’ [said the Savage].

‘We don’t,’ said the Controller. ‘We prefer to do things comfortably.’

‘But I don’t want comfort. I want God, I want poetry, I want real danger, I want freedom, I want goodness. I want sin.’

‘In fact,’ said [the Controller], ‘you're claiming the right to be unhappy.’

‘All right then,’ said the Savage defiantly, ‘I'm claiming the right to be unhappy.’”

This exchange, between the characters of John “the Savage” and the Controller, comes from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and shows the oppressive nature of a dystopian society. Dystopian fiction is one of many genres of literature and film. If you have ever read books within this genre, you might have seen connections between them in the setting of the story, the characters themselves, and the themes the authors try to portray.

Readers tend to see these worlds as bleak, the characters as under-developed, and some of the themes as unsatisfactory to a modern audience. This is not without design: the genre lends itself to bleakness, and thrives on it; after all, the best way to warn us against a potential future is to make it seem unappealing. Many authors do this by taking a pessimistic view of humanity or omitting an obvious savior. Others might set up a fatalistic society based on tyranny.

Regardless, I propose another way of reading dystopian fiction other than through a lens of pessimism or melancholy; instead, one that reinforces the beauty of what God has made in this world.

I will argue this for three reasons: first, because the flattened worlds of dystopian fiction can point us to the fuller reality of our existence; second, because dystopian fiction shows us various aspects of human nature that should be imitated by Christians; and third, because the absence of a true hero in most dystopian stories can reflect the reality of the Christian life.

A Brief History of Dystopian Fiction

Many forms of literature and media present dystopian worlds, so the term may be a familiar one. In a paper by María Rosso, she describes dystopia as able to depict cataclysmic worlds that then become warnings to the reader. While it can be difficult to see God’s goodness within these fictional, broken worlds, I will attempt to show that this is possible.

In order to understand dystopian fiction we must trace its history back to its literary cousin: utopian fiction. The concept of utopia has been around for ages. In the early 16th Century, Sir Thomas More wrote his famous satirical work, Utopia, whose “name derives from [the] Greek but has a double meaning: ‘eutopia’ (good place) or ‘outopia’ (no place).” More presents the ideal city where “Everything…is public property, food and hospitals are free and all religions are tolerated.” However, this work was a commentary on culture rather than a factual work because, “whatever More’s personal views, he was certainly contrasting his ‘virtuous' Utopians with the less virtuous citizens of his own time.”

Prior to More, the philosopher Plato wrote about a similar concept. John Reynolds explains in his article about social utopias that:

“Plato set out to design what he believes to be the best society possible, one able to not only sustain itself, but to flourish. In order to do so, he states that it cannot be governed by anyone but a philosopher, because philosophers are those best able to discern what is just and what is not…Under the rule of a philosopher, Kallipolis [the city] would have to be a utopian society because, according to Plato, a philosopher is the best ruler possible, and therefore would govern the best city possible, a utopia.”

There are those who would suggest that Plato was in fact portraying a dystopian society, rather than an ideal city. I would disagree. In the government Plato lays out, there are rulers who want a true good for their people—not to rule them for the sake of control, but rather for the sake of, in a word, perfection of the whole. ,.

It was not until the early 20th century that dystopian fiction emerged as a genre, and it began with science fiction. C.S. Lewis’ On Stories and Other Essays on Literature helps to explain the bridge between fiction and dystopia. “The name scientifiction, soon altered to science fiction, began to be common” during Lewis’ life, and he divides this genre into different categories.

The first includes stories based upon speculation. This type is included in many genres, and Lewis describes it as a way for imagining situations based on science and fact with the author catering to the readers. We see this occurring in Homer’s Odyssey, and Virgil’s Aeneid.

The second is the eschatological one, which has to do with the future and explores what our species could become if detrimental aspects of society are not changed or are changed too much. In this category we would find books such as Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games or James Dashner’s Maze Runner.

These subspecies are crucial to the idea of a dystopian world: authors create societies that are usually set in the future, and then provide instances of what could happen if something disastrous or experimental occurred, thus warning the reader against it.

In his introduction to Fahrenheit 451, Neil Gaiman writes,

“This is a book of warning. It is a reminder that what we have is valuable, and that sometimes we take what we value for granted…‘If this goes on…’ is the most predictive…although it doesn’t try to predict an actual future with all its messy confusion. Instead, ‘if this goes on…’ fiction takes an element of life today, something clear and obvious and normally something troubling, and asks what would happen if that thing, that one thing, became bigger, became all-pervasive, changed the way we thought and behaved…it’s a cautionary question, and it lets us explore cautionary worlds.”

1984

Dystopian literature is characterized by bleak societies and empty worlds. But what are we to do with these sad, broken societies other than think, “Oh well, at least I don’t live there,” and move on, not looking back to see if there are bits of light scattered in the rubble of these stories? Dystopian books—at least, the ones that I have read—tend to be grim or disturbing in some aspects. This can lead to an air of pessimism in reading them, but I will show how there is another way of approaching them.

First, the flattened worlds of this genre can point us to a fuller existence. George Orwell’s 1984, a classic dystopian novel, contains a severely flattened world and is thus often read pessimistically, and for good reason. 1984 is set in the totalitarian state of Oceania. This state is governed by the all-controlling Party, which has brainwashed the population into an unthinking obedience to its leader, Big Brother. The book’s protagonist, Winston Smith, has the job of rewriting history and adjusting it to current political thinking. However, Winston’s longing for truth leads him to rebel secretly against the government. Winston starts to keep a diary, which is against state laws, and falls in love with another rebel, Julia.

To summarize the rest of the book, Winston is eventually caught and sent to the government for a “violent reeducation” where he endures imprisonment and torture. These methods, in breaking Winston physically, are also intended to destroy his dignity and humanity. Winston ends up betraying his lover, the action of which authorizes his release. Later, Winston finds that he no longer cares about Julia, and, as the book concludes, he realizes that, “the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother.” Winston falls prey to the totalitarian society in which he was but a pawn.

It’s bleak. It is depressing. But in this book, I want to focus on the stifling of human nature and the absence of love to point us to the beauty in this story. The government of Oceania, Ingsoc, controls its citizens by conditioning the entire population; the individual is taught from birth that Big Brother is the leader and is constantly watching their every move. As Christians, we might shudder at this illustration of persuasive oversight, and yet there are similarities as well as differences between this domineering manifestation of Big Brother and the overwhelming presence of God.

As citizens of Oceania, the individuals are created for the purpose of being cogs in a machine; they are meant to work for the government, to obey the government, and in a sense, to worship the government. Comparatively, as human beings, we were each created “Imago Dei”—in the image and likeness of God. We are called to be like and glorify Him. I am not saying that God is our version of Big Brother, as that would be heretical. God is not a totalitarian leader who looks to own or even destroy those he rules. But there are some similarities between the two: the people of Oceania are told to believe in and love an entity that they do not understand; similarly, Christians are called to love, obey, and have faith in a being we cannot see but believe in anyway. What makes God different is that He loves us. Big Brother cannot love: he is pure propaganda. He has no love and he is not a true leader. This lack of love in Big Brother should prove a counterexample to the loving nature of God.

Additionally, God created his children to love. The lack of love in this book is crucial because it shows a lack of humanity. 1984 presents a very bleak outlook on the human race, one centered on control in order to keep power. In contrast, we as Christians are called to live for the kingdom of God which is not a tyrannical, totalitarian government, but one governed by a benevolent King.

In reading novels such as 1984, we are reminded of the Kingdom of God that we as Christians anticipate. We are able to compare the empty worlds of dystopian fiction with the world that God has created by seeing how the population responds to those in power. In dystopian worlds, the citizens are meant to conform and obey mindlessly. The quality of life that they experience is appalling; there is no beauty or love that they can enjoy, nor are there hardships in their lives. Things are too easy yet they are constantly watched, and they cannot see that this is damaging. In the world we live in, we can see that it is broken and in need of saving. We are able to see where we need redemption, and we have hope and knowledge that we have a Savior who truly loves us rather than a fictional leader who only wants control.

Second, though it seems depressing and bleak, dystopian fiction shows us aspects of human nature that should be imitated by Christians. Dystopian novels often depict their heroes as rebels against an overbearing government. While in the contexts of the stories this quality can be good, it is not what Christians aim for in life. To be human is to be like God, loving him and doing his commands; in dystopian societies, to be human is to fight against everything the government stands for.

Brave New World

This theme becomes clear in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World with the character of John the Savage, whom I referenced earlier. This book, written between the World Wars and heavily influenced by science and technology, portrays a dystopian society ruled by conformity and obedience. The entire world is brought under this control with the exception of the “Savage Reservations” which are the homes of those who live apart from the World State.

One of these “savages,” John, wants to experience life in the outside world. John is an outsider in the Reservation because his mother was a native to the World State. But when John goes into the Society, he finds that he is even more of an outsider there. He has been rejected by both the Reservation and the World State, and yet he is still the most human character in the book.

John argues with the World Controller of Western Europe, Mustapha Mond, claiming the right to things like danger, freedom, goodness, and sin. John embodies part of what human nature is meant to be post-Fall, but he cannot embody what human nature was pre-Fall. There is no way to be human for John other than through hardship, which is his claim. He wants to live a certain way, but the government restricts his ability to do so; once again, John is an outsider. His humanity is stifled in this place and he no longer has any hope by the end. Even though John tries to fight against this world, he ultimately fails.

This is not a call for us to constantly fight against our government, but since we can see that these fictional governments are so corrupt, we can then see how a character would need to rebel against such a government in order to keep his or her humanity intact. From characters like John in Brave New World and Winston in 1984, we can glean attributes that are admirable while not taking away from the story: John’s faithfulness to his own beliefs and Winston’s recognition of brokenness and attempt to fight against it. These characters, who are part of a broken world, can point us to the reality of our existence which has the hope of being saved.

Our Only Proper Hero

My final point is that the absence of a true hero in most dystopian stories reflects the reality of the Christian life. Heroes are pivotal in all genres of books, whether historical, fantastical, or science fiction. One character is almost always picked to be the ideal savior, no matter how broken they are, because the world they live in creates a need for a world-changer or a rule-breaker—someone who will save the society from itself. Why do we need heroes? Why do we want heroes? In our secular society, we do not have one overarching hero. There is no one to root for in the hopes that he or she will fix everything and we can have a happy ending.

A hero can take many forms in literature. It could be a dashing knight or a young boy with extraordinary powers. But in dystopian fiction, the only potential heroes are broken, flawed, and often unsuccessful. If this sounds familiar, it should: it sounds like us. We do not succeed all the time, and we need saving from ourselves. But the Christian life is not concerned with making us into heroes; in fact, we are often far from heroic.

Heroes are what move the story along; their goals tell us how to read the book, their qualities show us what kind of character they are. In dystopian fiction, when a true hero is needed, a hero is lacking and the story ends in bleak ways with no possibility of Christian telos or proper happiness. Instead it ends with a never-ending cycle of supremacy and submission. With this hero deficiency, the reader is left in want of someone who will save the rest of the characters; but where there is no saving grace, there can be no redemption. Any possible hero that the genre presents is flawed, broken by the world he’s trying to save.

Brave New World does not have a hero. We might think it is Bernard Marx, the protagonist of the first half of the book, who shows some restraint regarding the norms of this society, but who ultimately gives up and gives in—much like Winston in 1984. The Savage John is the best hero candidate; he has not been conditioned by the state, he has a moral sense of good and evil, and most importantly, he longs for true relationships. This difference between John and the other characters in this book is what makes him ideal, but by the end, John finds that he cannot fix this society. He too is flawed and broken, incapable of effecting any lasting change.

When we turn back to reality after reading such a book, we can breathe a sigh of relief because we know that we have a Savior who loves us, who will never leave us in our own broken situations forever. This way of reading dystopian fiction can point us to Jesus, the hero archetype who is the only one who can truly accomplish what needs to be done. Jesus was sacrificed for his creation and became the atonement that we needed but could not possibly achieve. Only the one who made the world can fix what has been broken in it. What comes from knowing this is gratitude that God has not made our world like these stories—He did not set us up to fail. By reading novels like these, which do not contain true heroes, we are reminded to look forward to the coming of Jesus—the only one who could ever be a proper hero to us.

On Reading “Depressing” Books

Now there may be those who would ask, “Aren’t these books meant to be bleak? Aren’t they a warning to us to not create the futures they portray?” As I said earlier, this genre thrives off of bleakness, and so if we read them through a lens of hope, wouldn’t that miss the point of the genre?

Not necessarily. Stories are meant to teach us. We learn from reading about battles, we can be prompted to action from reading about history, and we can spark new ideas by reading fiction. While this genre may seem to promote and be consumed by desolation, it is a way for us to learn about how what we do affects how we live. It is a warning, it is a clue. It shows us how, even though it seems bleak, these books can help us understand consequences and our own actions regarding them.

You might be hesitant to agree with me. There are so many other genres that we could read to glean the same truths from, why would we want to read these depressing books in order to come to conclusions that we are taught in church, in school, or that we can read in historical texts or the Bible?

The answer I have is a simple one: most young adult readers that I have met are more likely to pick up and read a fictional or dystopian novel rather than a history book. Granted, there are exceptions, but most young adults prefer a fast moving story with relatable characters and an ending within 300 pages or less. Stories in history do not always work like this; there may be characters who we relate to, and sometimes there are happy endings, but history is very complex in that we have to decide for ourselves who is the antagonist or the protagonist, whereas in fiction, it is apparent to the reader which characters are set up to be the villain or the hero.

My research concludes that the most popular genres for young adult readers include fantasy, sci-fi, thriller, westerns, and dystopian fiction, among others. Within this list, there is no mention of a historical text or even historical fiction. In short, young adults are more likely to choose a fictional book of their own volition rather than a purely historical text.

So What?

In summary, we have been looking at how dystopian fiction should be read through a biblical lens. We saw, first, how our fuller reality is reflected in these flattened worlds, second, how dystopian fiction shows us admirable attributes in characters, and lastly, we observed how the absence of a true hero within this genre can hint at the need for the One in the Christian life.

But why does this matter? Why should dystopia or any other fictional genre impact the Christian life? It matters because literature is a pivotal part of society: it shapes our culture and our beliefs. The effect that it has over us is tremendous, but the deeper implication is how we could start to become the worlds that we read about. As Neil Gaiman points out, dystopian fiction can be a warning to the reader of what to change in order to avoid a certain future.

What remains is choosing a path to take from here. Do we continue to read this genre pessimistically? Do we forgo ever reading it again? Or do we choose to be more attentive to what we read and how it affects our lives? I have argued for the third. It may start out as trying to understand basic concepts, and then turn into making great, existential connections across genres. But even the smallest thing, the tiniest habit, the minimal effort given can lead to a broader understanding of and a greater love for these types of stories.

Millie’s Recommended Reading List

Dystopian fiction

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

1984 by George Orwell

Animal Farm by George Orwell

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins [trilogy]

The Giver by Lois Lowry [all 4 books]

The Maze Runner by James Dashner [1st book only]

Ready Player One and Ready Player Two by Ernest Cline

Miscellaneous research and sources

Plato’s Republic

The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien [trilogy]

The Basic Works of Aristotle

The Iliad by Homer

The Odyssey by Homer

The Aeneid by Virgil

Post(erity): “The Big Read”

Each week, I choose a post from the past apropos of something in the newsletter.

This week’s Post(erity) post, “The Big Read,” dates back to January 2007, when I was part of a book club that read Fahrenheit 451. I attempted a quick review (hardly as thorough as Millie’s above), writing it as a warning against censorship. An excerpt:

“Comparable to George Orwell's 1984 and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, Fahrenheit 451 is probably the most believable of these three ‘doomed future’ stories as it does not come across so ‘futuristic’ as it does ‘future-is-now’ in terms of plot and perspective. Of all three books, Fahrenheit 451 seems most organic in its storytelling, and this perhaps is what makes it more frightening to think that a few generations of bad decisions could very well cast us into a cauldron of censorship, a concept so foreign to us right now that it makes it all the more scary to think about and believe.”

That last line..whoa. Read the whole post.

Fresh & Random Linkage

“How Do Big Tech Giants Make Their Billions?” - In case you were wondering, here’s a visually appealing breakdown of the bounty of Big Tech companies.

“Who We Spend Time with as We Get Older” - This is an interesting chart of “flowing” data tracking who we spend time with (and when) across the decades.

“The Nine Sub-States of Illinois” - An excellent look at the subtle (and not so subtle) regional and cultural groupings within my home state of Illinois.

Until next time.

Why Subscribe?

Why not? Second Drafts is a once-a-week newsletter delivered to your inbox and it’s totally free. To receive additional monthly content (podcast, book review), subscribe for $5/month.

Keep Connected

You’re welcome to follow me on Twitter.