On Myths, Symbols & Mascots

We've just launched our second annual Veritas Online Film Festival. This year's challenge is to create, film, and tell some aspect of the backstory of our new mascot, Griff the Griffin.

For some, a symbol like a griffin may seem purely and simply a pagan symbol that stands for a religious tradition in opposition to Christ. Although the griffin has been used as a pagan symbol by some, no symbol has but one, inherent meaning. Our Board of Directors and I recognize this and have attempted to put words to our perspective concerning it.

Symbols mean what people think they mean – that’s what makes them symbols. Perhaps the best example of this assertion is the cross itself, the central symbol of Christianity. What would a Roman or a Jew (or, for that matter, just about anyone) at the time of Christ say the cross “meant” or “stood for”? The answer is undeniably that it represented the power of the Roman Empire to force its will on the world, and to do so in what is arguably the most inhumane method of execution that has ever been devised by the hearts of men: crucifixion.

But is that what we think of when we put a cross around our necks or see a cross on top of a church as we drive by? That certainly is not what the cross means or stands for to most Christians, including us. It is a symbol of hope and grace, not inhumanity and torture, a symbol of triumph, not defeat, for all who are in Christ. Its meaning, in other words, depends on the mind of the beholder. What it once meant to some is not what it now means to others.

As with most symbols, the griffin is no different in this regard. Other examples that come to mind are the Christmas tree and the Easter egg, both of which were originally pagan symbols that were co-opted by the Church and, arguably, redeemed. Indeed, a number of orthodox Christian theologians have noted that because pagans live in God’s world, many of their pagan rituals and myths and symbols wind up unintentionally reflecting something real and true that comes from Him (a common mythological theme, for instance, is resurrection, which inadvertently points to Christ, who is The Resurrection). They don’t mean to, but they can’t help it because they live in His world.

Some Christians, of course, cannot bring themselves to see even symbols like the Christmas tree or the Easter egg as anything but pagan, and thus they refuse to put up Christmas trees or to celebrate Easter (which itself is the name of a pagan goddess). According to this reasoning, America should also drop the eagle as our national symbol because the Roman Empire and Hitler’s Third Reich used the eagle as their symbols.

Even the symbol of a seemingly more "biblical" animal - the ram, for instance - doesn’t inherently “mean” any one thing, including “the Lord will provide.” That certainly isn’t what it means to the NFL football team that adopted it, nor is that what all people associate with this symbol when they see it. Some see a symbol of brutality and aggression (as in, “to ram” something), and still others mistakenly see it as a goat, a common symbol of Satan.

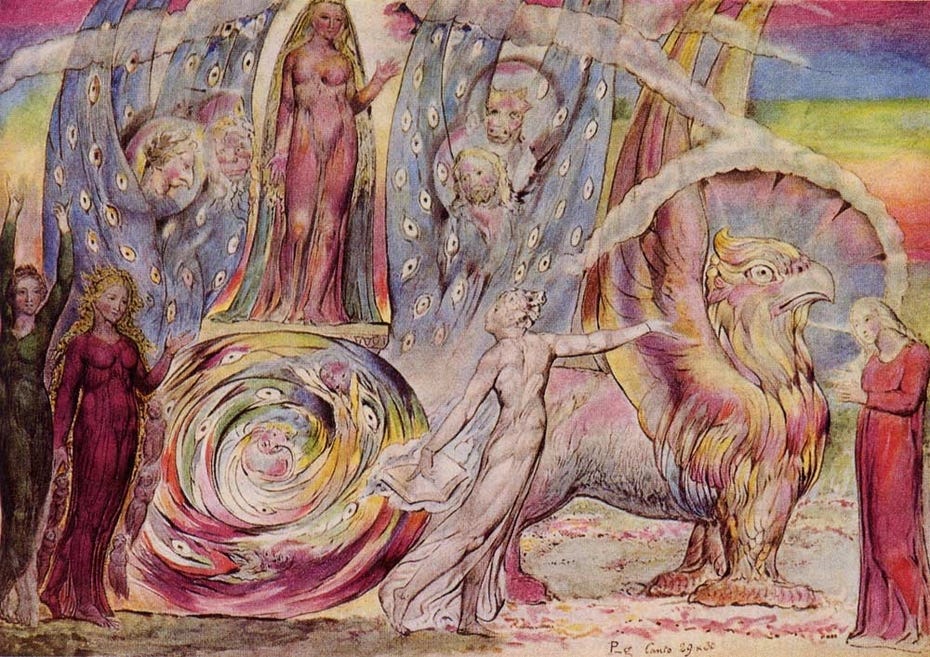

The griffin has stood for a number of different things throughout history, and it does not belong to any single culture. Since the middle ages, it has been used throughout western heraldry to symbolize strength and wisdom. In a number of famous works of western literature (including Dante’s Christian allegories), the griffin has even symbolized Christ Himself.

More recently, a secular institution, the College of William and Mary, has adopted the griffin as its mascot because it combines a “British symbol,” the lion, with an “American symbol,” the eagle, a combination that is consonant with the history and tradition of that college. Thus, the College of William and Mary sees in the griffin neither Greek mythology nor Christian allegory, but the nations of Great Britain and the United States of America. Are they wrong to see this? Not at all. This symbol, like all others, “means” to them whatever they think it means.

As Christians, when we look at the griffin, we don’t see the ancient pets of pagan gods or the patriotic emblems of contemporary nations. Rather, we see the biblical symbols of the lion and the eagle, which are used throughout Scripture to reference Christ Himself as the King (the lion) and as the divine Son of God (the eagle), as well as to reference two of the four gospels (Matthew and John) and certain virtues that have often been culturally associated with these animals (e.g., strength, virtue, wisdom).

These symbols also appear in prophetic visions about heavenly beings, such as the book of Ezekiel (chapters 1 and 10), and the book of Revelation (chapter 4). A lion is not always used in Scripture to refer to Christ, of course. In Daniel, for instance, a lion seems to be used to refer to a particular ungodly kingdom (not to mention being the intended means of Daniel’s own failed execution). But this simply underlines the point we made already, that a symbol’s meaning is not fixed, but is relative, changing, subjective, and contextual. That’s what makes it a symbol.

Part of our job as Christians is to take what has fallen and been distorted, including myths and symbols, and to redeem it. Christmas, Easter, and even the griffin are examples of this, but the same could also be said of classical education itself, which was “invented” by the Greeks but redeemed and “made right” by the Christians. Likewise, when we look at this mascot, we see biblical imagery, not pagan mythology (see Paul’s exhortation to the Corinthians about the acceptability of meat offered to pagan idols for a similar issue facing the early church).

The fact is, there is no mascot we will ever be able to choose for our school that, symbolically speaking, is without possible taint. However, as we have chosen the griffin - Griff the Griffin! - our hope is that our community and others recognize our mascot as one that symbolizes our aspiration to pursue, to love, and to guard treasure and priceless possessions like Knowledge, Wisdom, Goodness, and Beauty.

(“Beatrice Addressing Dante from the Car” by William Blake)