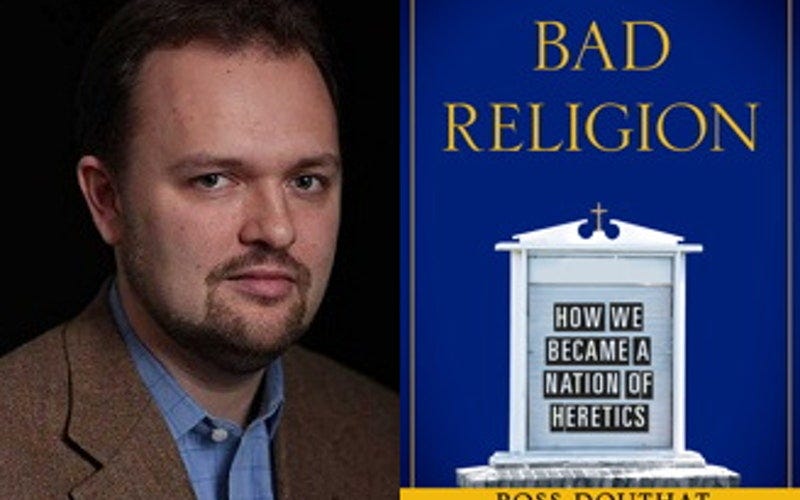

Review: Bad Religion by Ross Douthat

One of the benefits of getting older is reading books that bring context and perspective to one's experience of recent history. I remember initially thinking about this during my first year at the University of Missouri as I listened to my American history professor lecture on the Vietnam War. In his early 50s at the time (1989), my prof's passion for both the era and the book he had assigned to us (The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien) could not be denied.

Until that point, whether in high school or college, I had never taken a history class that had brought me to the present year; like most my age, Vietnam was about as far as we got, despite all that happened in the 1970s and 1980s. Attending class and doing the reading for this first college history course, I wondered what it felt like to read and study a book about a period of history one had actually lived through only twenty years previous.

This is probably why I enjoyed New York Times columnist Ross Douthat's Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics as much as I did. Not only have I lived through two-thirds of the past 60 years that Douthat primarily focuses on, but his analysis and contextualization of this period of time within the larger breadth of history (American and otherwise) is quite revealing of how we have arrived where we are religiously, politically, economically, and socially.

In his breakneck-paced prologue, Douthat summarizes his take and cuts to the chase as to where American Christianity is in 2012. Taking a page from The Reason for God by PCA pastor/author Timothy Keller (who wrote a glowing endorsement for the book), Douthat writes:

"America's problem isn't too much religion, or too little of it. It's bad religion: the slow-motion collapse of traditional Christianity and the rise of a variety of destructive pseudo-Christianities in its place...The United States remains a deeply religious country, and most Americans are still drawing some water from the Christian well. But a growing number are inventing their own versions of what Christianity means, abandoning the nuances of traditional theology in favor of religions that stroke their egos and indulge or even celebrate their worse impulses. These faiths speak from many pulpits - conservative and liberal, political and pop-cultural, traditionally religions and fashionably 'spiritual' - and many of their preachers call themselves Christian or claim a Christian warrant. But they are increasingly offering distortions of traditional Christianity, not the real thing." (p. 4)

From here, Douthat launches out on a 125-page reconnaissance, skimming the fields of the early twentieth century before landing the plane post-WWII during the Eisenhower years. Holding forth four personalities - neo-orthodox intellectual Reinhold Niebuhr, evangelical evangelist Billy Graham, Roman Catholic bishop and broadcaster Fulton Sheen, and civil rights leader Martin Luther King - as responsible representatives of the (mostly positive) convergence of formerly-divided houses of mid-century Christendom, Douthat sets the stage for the locust years to come.

The aforementioned convergence began to slow and segregate during the turbulent 1960s, with trouble coming at the hands of both the accommodationists within the more mainline churches and the resisters within the more fundamentalist churches. Over the next 50 years, records Douthat, the pressures of questionable technological ethics, overt political partisanship, temptation from economic affluence, and a "waning of Christian orthodoxy had led to the spread of Christian heresy rather than to the disappearance of religion altogether." (p. 145)

To quote G.K. Chesterton: "When people turn from God, they don't believe in nothing - they believe in anything." These "anything" beliefs are what Douthat uses the second half of his book to investigate and address. And, while he is extremely fair, he pulls no punches taking to task the Christian heresies propagated by liberal scholars (i.e. Bart Ehrman), prosperity gospel preachers (Joel Osteen, et. al.), "God Within" mystics (Deepak Chopra, Oprah), and American nationalists (Glenn Beck, David Barton). The pace of the book slows a bit here, but only because Douthat is thorough in his approach.

Finally, Douthat ends his book with a chapter of conclusion entitled "The Recovery of Christianity," offering "four potential touchstones for a recovery of Christianity." While he rightly handles what he calls "postmodern opportunity: the possibility that the very trends that have seemingly undone institutional Christianity could ultimately renew it," he stumbles a bit in making a distinction between the "emerging" and "emergent" church (they are different) as part of that possible solution, but his other three options are interesting to consider and he presents them with a heartfelt hope for change.

My only other critique of the book has to do with Douthat not always drawing as much separation between Christianity and Mormonism as I would like to see. While he seems to understand that the latter is not just a "funky" subset of the former, I was surprised by occasional "doctrinal issues aside" language used that seemed to minimize any differences between the two, thereby occasionally giving Mormonism more theological credibility than orthodoxy allows.

That said, Douthat's scholarship is well-researched, yet his writing is still very accessible to a popular audience, efficient in thought and prose and briskly readable. And, while his historical interpretation is impeccable, he is certainly no slouch in walking through the nuances of doctrinal debates either, whether they be of the Protestant or Catholic variety (Douthat himself is a practicing Catholic, but he cuts the Vatican no slack, nor does he outright diminish contributions of the Reformers).

Highly recommended.