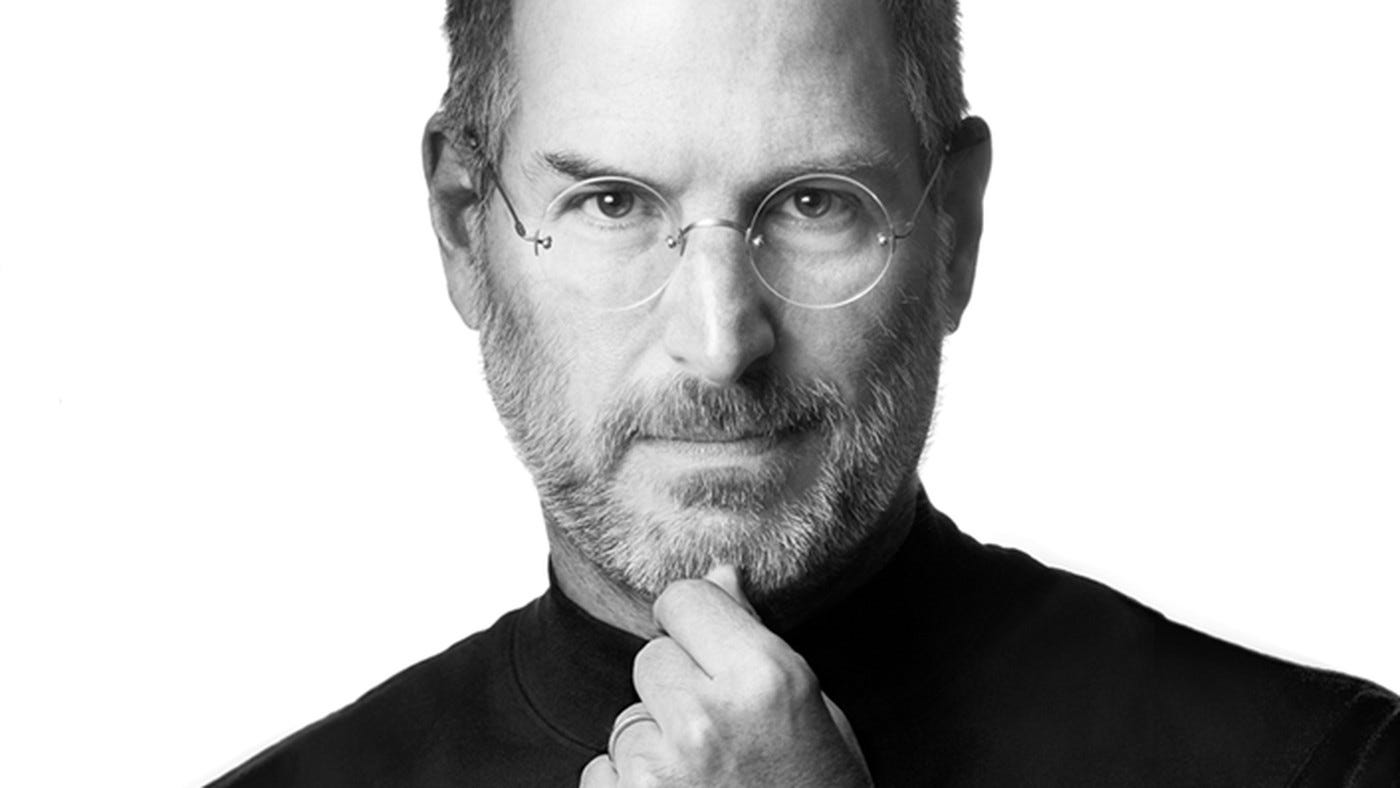

Review: Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

"He was an enlightened being who was cruel. That's a strange combination."

Chrisann Brennan (Steve Jobs's first girlfriend and mother of his first child, Lisa)

At last count, the Dunham family has accumulated 10 Apple products: 1 iMac desktop, 2 laptops (Pro and PowerBook G4), 1 iPad, 2 iPhones, 1 iTouch, and 3 iPods (2 Nanos and 1 Shuffle). One could say we've drunk the Apple Kool-Aid to the dregs: we love the products, have little to no trouble with them (other than sharing), and are big Apple advocates/evangelists (as of this Thanksgiving, we'll have convinced and equipped both sets of grandparents to go Mac).

Indeed, we meet the criteria for membership in the so-called Apple Cult, but this didn't make reading Walter Isaacson's painfully honest 600-page biography of Apple's founder, Steve Jobs, any easier. Even as I write this (on my MacBook Pro), I wonder to what degree my own desire for digital enlightenment supported the cruelty that produced it.

Though the first 50 pages of Isaacson's book seem clunky (especially when compared with his other biographical works like Benjamin Franklin and Einstein), part of this had to do with the fact that I was reading a completed biography of a man who had just died two months previous (Jobs had asked Isaacson several years earlier to start work on his biography when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer). For this reason - combined with the fact that forty years of my life had overlapped with much of Jobs' work during his 56 years - it was a different experience than reading about more historical personalities who lived and died 200, 100, or even 50 years previous.

But examples of Jobs's harsh leadership style didn't help, either:

"(Jobs) was flying high, but this did not serve to make him more mellow. Indeed there was a memorable display of his brutal honesty when he stood in front of the combined Lisa and Macintosh teams to describe how they would be merged. His Macintosh group leaders would get all of the top positions, he said, and a quarter of the Lisa staff would be laid off. 'You guys failed,' he said, looking directly at those who had worked on the Lisa. 'You're a B team. B players. Too many people here are B or C players, so today we are releasing some of you to have the opportunity to work at our sister companies here in the valley.'

Bill Atkinson, who had worked on both teams, thought it was not only callous, but unfair. 'These people had worked really hard and were brilliant engineers,' he said. But Jobs had latched onto what he believed was a key management lesson from his Macintosh experience. You have to be ruthless if you want to build a team of A players. 'It's too easy, as a team grows, to put up with a few B players, and they then attract a few more B players, and soon you will even have some C players,' he recalled. 'The Macintosh experience taught me that A players like to work only with other A players, which means you can't indulge B players.'" (p. 181)

Here's another recollection - same song, different verse:

"Right after he came back from his operation, he didn't do the humiliation bit as much,' (chief software engineer Avadis 'Avie') Tevanian recalled. 'If he was displeased, he might scream and get hopping mad and use expletives, but he wouldn't do it in a way that would totally destroy the person he was talking to. It was just his way to get the person to do a better job.' Tevananian reflected for a moment as he said this, then added a caveat: 'Unless he thought someone was really bad and had to go, which happened every once in a while.' Eventually, however, the rough edges returned." (p. 461)

It was interesting how Jobs's Zen Buddhist beliefs informed (or didn't) his life. Isaacson records Jobs' estranged daughter, Lisa (for whom his first computer was named), asking Jobs why he was so preoccupied with creating great material products when Buddhism does not recognize material things as being real or mattering? Jobs was quiet and never answered the question, but one could tell the inconsistency bothered him.

Though Jobs did not necessarily create anything completely "new" in the digital world (author Malcolm Gladwell asserts as much in the New Yorker a few weeks ago in his article, "The Tweaker: The Real Genius of Steve Jobs"), Jobs did redesign average products and redesign entire industries with his drive. In the last chapter of the book, Isaacson lists Jobs's contribution over three decades (some of his descriptions below could be given somewhat to hyperbole):

The Apple II, which took (Steve) Wozniak's circuit board and turned it into the first personal computer that was not just for hobbyists.

The Macintosh, which begat the home computer revolution and popularized graphical user interfaces.

Toy Story and other Pixar blockbusters which opened up the miracles of digital animation.

Apple stores, which reinvented the role of a store in defining a brand.

The iPod, which changed the way we consume music.

The iTunes Store, which saved the music industry.

The iPhone, which turned mobile phones into music, photography, video, email, and web devices.

The App Store, which spawned a new content-creation industry.

The iPad, which launched tablet computing and offered a platform for digital newspapers, magazines, books, and videos.

iCloud, which demoted the computer from its central role in managing our content and let all of our devices sync seamlessly.

And Apple itself, which Jobs considered his greatest creation, a place where imagination was nurtured, applied, and executed in ways so creative that it became the most valuable company on earth.

To Isaacson's (and Jobs') credit, the book is as honest as one might hope for in a biography. Isaacson does a good job drawing out the themes that play through Jobs's life: his life-long insecurity at having been given up for adoption as a newborn; his passion for minimalist, beautiful design; his philosophy that closed platforms make for ultimately better user experiences than open ones (Microsoft); and his belief that people don't know what they want until they see it (or in Jobs's mind, until he shows it to them).

While I've always thought of Jobs as the last of a dying breed of innovative entrepreneurs (as so wonderfully - if a bit expletively - captured in this brilliant news clip in The Onion), I see with new eyes what the price of progress actually was at Apple. Was it worth it? Many of those interviewed seemed to believe so, but more than a few of these same people also seemed relieved that Steve Jobs was gone.

iSad.