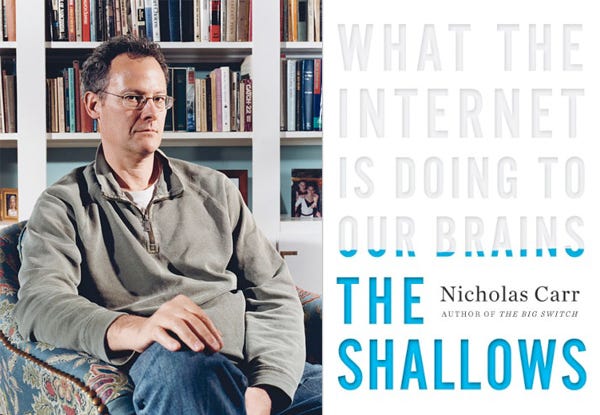

(The following is the second of a three-part review (here are parts 1 and 2) of one of the more important books in the past ten years: The Shallows by Nicholas Carr.)

In chapter 7, titled “The Juggler’s Brain,” Carr clarifies what he (with the help of brain researchers) think the Internet is doing to our brains. He writes:

“One thing is very clear: if, knowing what we know today about the brain’s plasticity, you were to set out to invent a medium that would rewire our mental circuits as quickly and thoroughly as possible, you would probably end up designing something that looks and works a lot like the Internet. It’s not just that we tend to use the Net regularly, even obsessively. It’s that the Net delivers precisely the kind of sensory and cognitive stimuli—repetitive, intensive, interactive, addictive—that have been shown to result in strong and rapid alterations in brain circuits and functions. With the exception of alphabets and number systems, the Net may well be the single most powerful mind-altering technology that has ever come into general use.” (p. 116)

He continues:

“The Net also provides a high-speed system for delivering responses and rewards—’positive reinforcements,’ in psychological terms—which encourage the repetition of both physical and mental actions. When we click a link, we get something new to look at and evaluate. When we Google a keyword, we receive, in the blink of an eye, a list of interesting information to appraise. When we send a text or an instant message or an email, we often get a reply in a matter of seconds or minutes. When we use Facebook, we attract new friends or form closer bonds with old ones. When we send a tweet through Twitter, we gain new followers. When we write a blog post, we get comments from readers or links from other bloggers. The Net’s interactivity gives us powerful new tools for finding information, expressing ourselves, and conversing with others. It also turns into lab rats constantly pressing levers to get tiny pellets of social or intellectual nourishment.” (p. 117)

One could argue (or at least I will here) that a better solution to kids' ever-increasing struggles with Attention Deficit Disorder could be technology reduction rather than Ritalin prescription. Think about it: When a kid has trouble paying attention in class, rarely is there ever a discussion about doing away with smart phones or Facebook; medicines are started, adjusted, or switched, but God forbid we address ubiquitous, long-term technology exposure as part of the problem (this would, after all, seemingly punish the kid whose friends are all constantly connected, not to mention become inconvenient to parents who think of their kids’ cell phone as a digital leash).

Consider this from Carr:

“The Net commands our attention with far greater insistence than our television or radio or morning newspaper ever did. Watch a kid texting his friends or a college student looking over the roll of new messages and requests on her Facebook page or a businessman scrolling through his emails on his BlackBerry—or consider yourself as you enter keywords into Google’s search box and begin following a trail of links. What you see is a mind consumed with a medium.” (p. 118)

Other effects our brains may suffer due to frequent Net exposure: we fear “our social standing is, in one way or another, always in play, always at risk” (p. 118); we suffer from constant distractedness that the Net encourages (“distracted from distraction by distraction”) (p. 119); this online distraction “short-circuits both conscious and unconscious thought, preventing our minds from thinking either deeply or creatively” (p. 119); as a result, we suffer “cognitive overload,” for “if working memory is the mind's scratch pad, then long-term memory is its filing system,” and “the depth of our intelligence hinges on our ability to transfer information from working memory to long-term memory and weave it into conceptual schemas.” (p. 124)

True, concedes Carr, “Research shows that certain cognitive skills are strengthened, sometimes substantially, by our use of computers and the Net. These tend to involve lower-level, or more primitive, mental functions such as hand-eye coordination, reflex response, and the processing of visual cues.” (p. 139) Is this good news or bad news? Carr answers the question this way: “The Net is making us smarter...only if we define intelligence by the Net’s own standards.” (p. 141)

I could go on (and Carr certainly does) with more research and examples to make his case, but for me, the point is this:

“The development of a well-rounded mind requires both an ability to find and quickly parse a wide range of information and a capacity for open-ended reflection. There needs to be time for efficient data collection and time for inefficient contemplation, time to operate the machine and time to sit idly in the garden...The problem today is that we’re losing our ability to strike a balance between those two very different states of mind. Mentally, we’re in perpetual locomotion.” (p. 168)

One of the biggest takeaways for me from the book is my need to educate students (and parents) about what really is happening to our brains as a result of the medium and not just the message of our technology. This must go beyond quoting studies of teen cell phone use and time spent on Facebook. I have to figure out how to practically help them understand the science of the reality, backing up the latest research with Scripture's timeless call to “take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5).

At minimum, this is easily an entire period or maybe a multi-day mini-unit at the beginning of the school year; at maximum, it’s an on-going conversation in and out of the classroom the whole year round. Whichever, I don’t plan to have the conversation via email.