Dear Reader,

I’ve been a little overwhelmed this week. I’m still working on the memoir (which was to be done at the end of December and which I now hope to complete by the end of January); play practice for Orpheus Ascending started this past Wednesday and rehearsals run (more or less) five nights a week between now and the end of March; and, I put in some extra work this week on January’s subscriber podcast that will drop tomorrow (more on that below).

But those are just details. The actual reason I’m overwhelmed is the willingness of 42 of you to become paid Second Drafts subscribers! I had no idea what was even possible, but I’m so grateful for those readers who signed on for the “extras” I have planned this year in addition to receiving Friday’s normal newsletters. It’s more than a little humbling. Thank you!

Don’t forget you’re always welcome to subscribe if you haven’t already (just click the button below). In whatever way you’re here, know that I’m glad you are. Enjoy this week’s Second Drafts, and as always, thanks for reading.

Craig

P.S.: Comments are turned off. You’re always welcome and encouraged to email me directly with feedback, ideas, links, etc. at cmdunham [at] gmail [dot] com. Just know that, unless you tell me not to, I may quote you here (though it will always be anonymously).

Note for Paid Subscribers

For paid subscribers this month, look for these extras between now and the end of January:

Saturday, January 22 - For the 49th anniversary of Roe vs. Wade, Peaches and I interview friend and fellow Trinity Church member, Catherine Aubrecht. In “The Discussion You’ve Always Wanted to Have about Abortion,” we talk about the Christian view of human life, men behaving badly, feminism as a secular creed, the pro-choice/pro-life debate, and God’s redemption of her life despite her own past abortions.

Saturday, January 29 - Peaches and I are looking forward to writing an in-depth review of a collection of essays titled, The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry, selected and with an introduction by Paul Kingsnorth. If you’re not familiar with Wendell’s writings (he and we are on a first-name basis, though we don’t think he knows that), this will hopefully be a good place to start.

Hot Takes

A quick look at a few news stories this week:

“Ghislaine Maxwell Ends Fight to Keep Eight ‘John Does’ Secret, Court to Decide Whether Names Should be Unsealed” - As much as I think Ghislaine Maxwell probably deserves whatever punishment she gets for her sex trafficking ways, I’m almost certain that those for whom she did it deserve a harsher penalty. We just need their names, and it may be that we’re a step closer to getting them.

“Ghislaine Maxwell will no longer fight to keep the names of eight 'John Does' secret and will leave it to the court to decide whether the names should be unsealed, according to a January 12 letter to federal Judge Loretta Preska of the Southern District of New York. The documents containing the names are connected to a 2015 defamation case brought by Virginia Roberts Giuffre, who claimed (Jeffrey) Epstein sexually abused her while she was a minor and that Maxwell aided in the abuse. The case was settled in 2017.”

I confess there are a few names that I want to see on that list - some of our so-called cultural “elites” who have gone their entire lives getting away with corruption, abuse, possibly even murder, and perhaps sex trafficking. I agree with Giuffre's attorney and the brief she filed on Wednesday, arguing for the names to be revealed:

“[G]eneralized aversion to embarrassment and negativity that may come from being associated with Epstein and Maxwell is not enough to warrant continued sealing of information. This is especially true with respect to this case of great public interest, involving serious allegations of the sex trafficking of minors,’ Guiffre attorney Sigrid McCawley wrote.

Now that Maxwell's criminal trial has come and gone, there is little reason to retain protection over the vast swaths of information about Epstein and Maxwell's sex-trafficking operation that were originally filed under seal in this case.”

I hope the court makes this happen. And I also hope that someone takes more responsibility for Ghislaine Maxwell’s viability in prison in case they need her to testify against some very evil and powerful people. We don’t need another “suicide.”

“Canadian Woman Pauses to Take a Selfie While Rescuers Hurry to Save Her From Car Sinking Into Icy River” - I’m not much of a selfie fan, but I know plenty of folks who are. If I have to take a picture (which is not my favorite thing to do), I prefer it to be an “us-ie” with other people involved; too much of the other seems like vanity unless it’s self-deprecating, which is why, I suppose, I have a soft spot for this seemingly selfish woman in Ottawa who had folks up in arms about her actions:

“A Canadian woman found herself in a precarious situation — standing on the roof of her car as it slowly sank beneath the surface of an ice-covered river — but not so precarious that she couldn’t stop and take a selfie. According to a report by CTV News, the woman was driving her car on the frozen Rideau River in Ottawa around 4:30 pm Sunday when it broke through the ice and started sinking into the frigid water below. Local residents came to her rescue, using a kayak to allow her to get off the roof of her car shortly before it sank entirely below the surface, and pull her to where the ice was more solid. Emergency crews had been called but the woman declined treatment at the scene.”

Yes, she did something stupid (racing her car around on a semi-frozen river), but once the car came to its watery handstand and she was safely standing on its tail end, I’m not sure there was as much danger for her or others as media reports said there was. She was just waiting. Why not take a picture?

For comparison, it reminds me of what Vincent Van Gogh did after he got depressed, drunk, and cut off his ear - he painted a self-portrait of his stupidity for all to see. Likewise, I don’t fault this woman’s taking of a selfie; the stupidity was already done. If capturing stupidity isn’t the true and good purpose of a selfie, what is?

Streets of Bakersfield

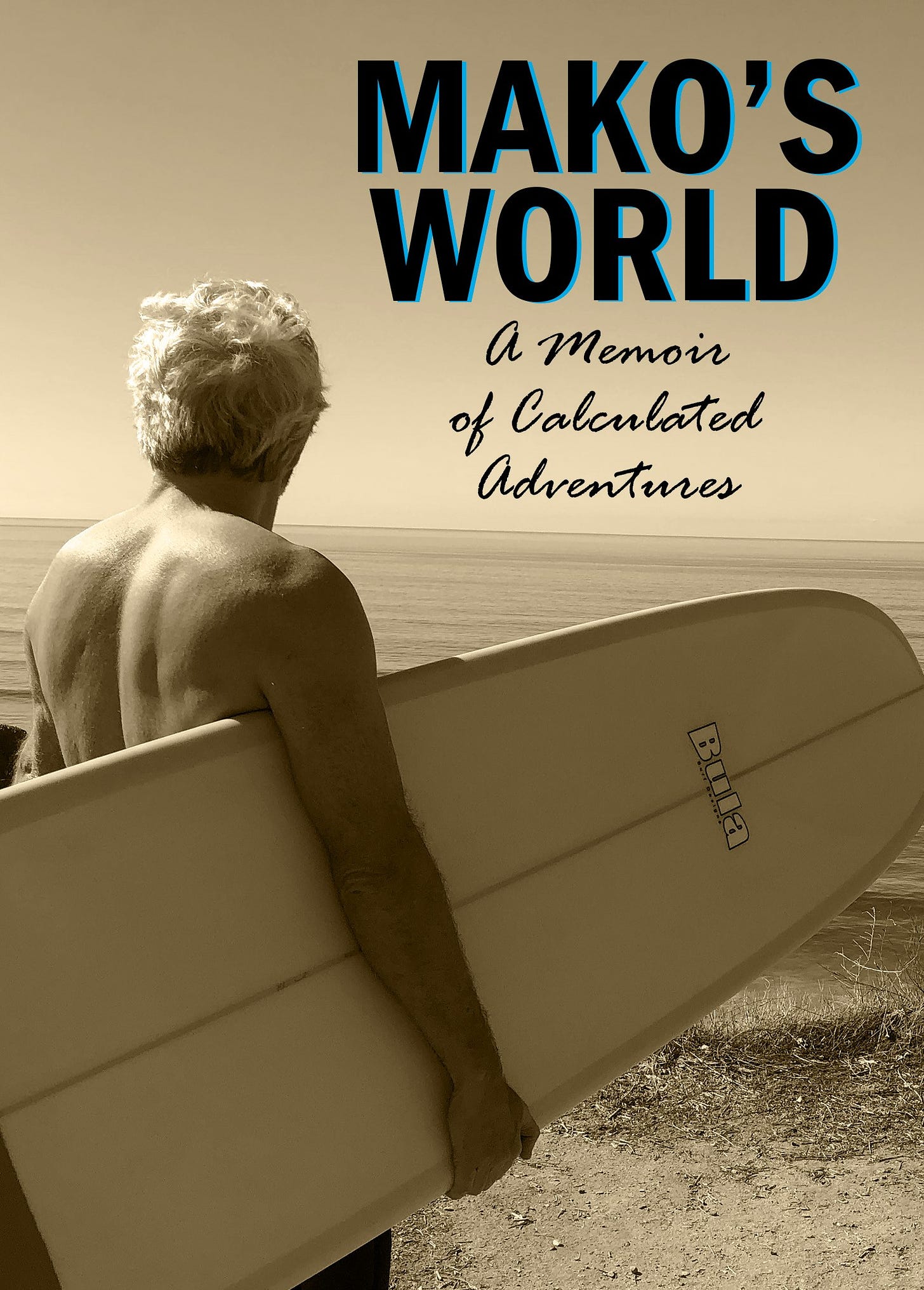

It’s been seven weeks since I posted an excerpt from Mako’s World: A Memoir of Calculated Adventures, the memoir I’m helping a friend write. “Sharky” was the first excerpt I shared in mid-October; “Running (from) Drugs in Sinaloa” was the second, posted in early December. This third and final offering, “Streets of Bakersfield,” chronicles the summer of 1983, when my friend was 22 and interned in the oil fields near Bakersfield, California. (Trigger warning: this story contains vivid details from oil field culture not suitable for young children).

Streets of Bakersfield

“You don't know me but you don't like me,

You say you care less how I feel

How many of you that sit and judge me

Ever walked the streets of Bakersfield?”—“Streets of Bakersfield”

by Homer Joy“Casualness leads to casualties.”

—Mako

McKittrick, California, is 45 miles due west of Bakersfield and right in the heart of California’s oil fields. The Associated Oil Company discovered these fields in 1911, and by 1912, President William Howard Taft, concerned about the long-term availability of petroleum for the U.S. Navy, designated the region as the nation’s first Naval Petroleum Reserve. This lasted until the mid-1970s, when, in response to the 1973-1974 Arab Oil Embargo, Congress passed the Naval Petroleum Reserves Production Act of 1976, authorizing full commercial development of the Reserves, with revenues deposited in the U.S. Treasury.

One of the largest of the Federal properties, Elk Hills, became the largest (in terms of production) oil and natural gas field in the lower 48 states at that time. Just west of Elk Hills, J. Paul Getty made his billions in oil drilling near McKittrick. I’d never heard of Elk Hills or Getty Oil until I went to a job recruiting fair at UC, Santa Barbara, where I got along better with the representative from Getty Oil than the ones from companies like Hewlett-Packard (HP) or National Cash Register (NCR). Somehow, the rep talked me into a summer internship drilling oil that involved wearing coveralls, steel-toed boots, gloves, “Smokey the Bear” hardhats, and getting covered in oil all day, every day, in 112-degree temperatures.

Life in the Oil Fields

For the first three weeks of that summer, I lived in a Motel 6 until the company moved me and a couch in with two guys from Oklahoma. These two were like Felix and Oscar of The Odd Couple, and being somewhere in between their respective psychoses, I got along fine with both. When we weren’t on the job, we spent the majority of our time lifting weights, eating chicken, and drinking gallons of milk and plenty of beer.

As part of the oil field crew, I had one tool—a 48-inch pipe wrench that I could barely lift—to unscrew pipe all day as part of lubing the threads of the pipe before sending them back down, which was part of good “well maintenance.” It was miserably hot work, made even more miserable by the oil field clientele and their preoccupation (past and present) with crime, prostitution, and hazing. Most mornings, a highway patrolman would show up onsite to arrest someone, but for those who avoided the law and made it to the 3:30 quitting time, they looked to have some fun with the new guys - the “worms,” as we were called—for a different version of “lubing”—de-pantsing the victim and running a wire brush with copper lube from front to back.

Any time the group set their sights on me to “lube the worm,” I would wriggle free and take off running. This, of course, never deterred their efforts to carry out their plans, and many of them enjoyed hopping in their trucks to come after me, but I was always able to run my way around the uneven fields and hills and washes to make it impossible for them to catch me in their vehicles. Sometimes (and this is not an exaggeration), I would have to run what had to be at least four to five miles at a time, veering around out in the desert before they would finally give up the chase, and while they made the attempt multiple times, they thankfully never caught me.

Perhaps because they were tired of playing roadrunner and coyote, they turned to a new form of hazing: fighting. Nearly every afternoon at the end of the day, I got thrown into a circle of guys with some local whose directive was to beat me to a pulp. The taunts of, “Come on, college boy,” rang in my ears as an inevitably bigger guy was chasing me around the ring. While I was a trained boxer (thanks to my father’s childhood efforts), I was a better wrestler, so my strategy was always to take the fight to the ground and then perform a half-nelson, thrusting one arm under my opponent’s arms and placing my hand on the back of his neck in order to grind his face into the dirt. Inevitable cries of, “That’s not fair,” did my challengers no favors in the popular opinion of our spectators, who loved seeing me win even as they plotted anew how to punish me for my success.

One day, two guys known to prefer men over women cornered me and asked me if I knew what a “bulldog nelson” was? Taking both of them to hold me, one of them temporarily got me in a full nelson with both arms and, for lack of a better word, started dry humping me from behind until I broke and spun out of the hold. We all had a good laugh, but mine was more nervous than theirs.

A few days later, these same two offered me a ride ostensibly to the company yard. I hopped in the cab of the truck between the two of them, but after a few miles, I noticed we were not headed in the direction we should have been going and mentioned so. The man driving laughed and said, “We’re taking you out to the oak tree for a real bulldog nelson.” The other man laughed and smiled.

Though outnumbered, I knew I couldn’t be intimidated if I wanted to avoid being raped. I laughed, too, then looked through the windshield and, as matter-of-factly as I could and said, “Well, if that’s what you think is going to happen, I probably need to let you know that one of you will be blind and the other one will die this afternoon. I’m not going to tell you who will get what, but I know how to do both.” I then turned and smiled at each of them and went back to quietly looking through the windshield.

The two looked at me and then each other, giggling nervously without saying another word. By the time we got to the oak tree, the driver circled the truck around it and we drove back to the company yard in silence. Later, my supervisor told me that one of the guys, perhaps out of spite or embarrassment, tried to convince him to put me on the night shift. My supervisor told him no. When I asked him why he declined the request, he said, “You don’t want to be on the night crew. Those guys carry guns.”

Charlie

Later that summer, I had a girlfriend who was from McKittrick. Her mother liked me and wanted her daughter to marry me, an engineer, which is often the case for McKittrick mothers of daughters involved with guys working the oil fields. The reason? While dangerous, the jobs are very lucrative; starting pay then would have been the equivalent of roughly $150,000 in today’s dollars, plus $150,000 signing bonus in hopes that the employee would immediately buy a house and settle down, improving the chances of him sticking with the company.

My girlfriend’s father, however, was not big on engineers in general, or me specifically. One night, after having a fight with her father, she stayed the night, which caused me to oversleep and miss my ride to the fields the next morning. By the time I got to the yard, all the trucks had left, which was a problem, since my work partner and I were supposed to be overseeing a hot oil truck. Thankfully, another senior guy had waited for me, so I jumped in the truck just as we heard a huge explosion and saw an enormous plume of black smoke in the distance. We took off in the direction of the smoke and he maneuvered the truck like a Rally car, getting air over hills and drifting all four wheels around turns as we made our way to the site.

When we arrived, we saw men standing in shock at a huge fireball that surrounded one of the hot oil trucks. Apparently, Charlie, the owner of the truck, hadn’t run the blower to clear out the propane, so when the gas ignited, it blew off the piping and was now a four-inch-diameter jet of fire shooting out of the truck. I tried to make sense and reconcile what I was seeing in the midst of the chaos of the flames and batteries exploding everywhere, flying 60-70 feet in the air.

Suddenly, there was another giant explosion, the concussion of which knocked me flat on the ground and almost unconscious. It was a very surreal scene. I remember seeing a guy flying through the air some 30 feet above me looking like Batman with a cape (I discovered later that his “cape” was singed skin that had separated from his body). Though I was only an intern, I had been through enough of the summer to have learned that, if the fire jet didn’t get turned off soon, the tank could “bevy” and take out the fuel farm, and with it the entire town of McKittrick.

That’s when I looked up and saw Charlie—wearing nothing more than his coveralls and aluminum hat—walk straight into the fire stream and turn the jet off. There was another explosion then, and he was blown 30-40 feet from the truck, landing about 10 feet from where I was again sprawled on the ground as a result of the blast. Thinking I could pull him to safety, I ran over to Charlie, grabbed his arms, and began to pull, but he was completely charbroiled; his blackened skin separated from his forearms in my hands and his muscles looked like burnt chicken. His nose, lips, and eyelids were gone, and all his clothes were burned off, with only his belt and plastic headband still in place. I didn’t know what to do.

Another explosion. I picked myself up off the ground again and ran behind a nearby hill where a few other men were taking cover. Helicopters and fire trucks were starting to show up and foamed the fire to put it out. Charlie was still alive but couldn’t be moved due to his muscles being so burned and contracted. We prepared salt water soak cloths and applied them to his wounds and the whole time he was moaning and screaming, “Oh, Jesus. Oh, Jesus.” He died a few hours later. Batman fared a little better, but he ended up dying six months later from his injuries. The images of these two men haunted my sleep and gave me nightmares for two years.

A week after the hot oil truck explosion, a guy was up in the crow’s nest when the derrick underneath geysered and he was blown through the air and badly injured from the blast. The next week, I was asked to investigate a strange noise coming from a lower tank farm. Upon inspection, I discovered it was natural gas and sand escaping through a fissure in the earth so violently that it made a sound as loud as a jet engine. Had it ignited, the entire field I had just driven across could have gone up from the natural gas pocket below exploding, but more urgently, I discovered I was standing over a large cavern of gas that could have collapsed.

That was it for me. Hands shaking, I drove back to the main office and went in and asked for an office job. I was put in an air-conditioned trailer and spent my days working on reservoir calculations and forecasting oil flows. I was surprised by how basic and rudimentary the work was, but I didn’t care; if my internship in the oil fields had taught me anything, it was that I did not want to work in the oil fields.

My work partner the week of the hot oil truck explosion had been a Vietnam veteran who was empathetic to all I had just been through. Randy had hair down to his shoulders and a full beard, and nobody messed with him because they knew where he’d been and that he understood what it was like to look death in the face. I was glad for his sympathy when I told him how I woke up night after night seeing Charlie—one moment a normal human being, the next a piece of meat cooked to a crisp—burn to death. The term hadn’t been coined yet, but I must have had some form of PTSD—post-traumatic stress disorder—from seeing Charlie’s safety helmet melted away and the plastic band that held it on his head fused into his forehead. All of his clothes—with the strange exception of his leather belt—had instantly burned off, exposing the vulnerability of his humanity—a sight I couldn’t unsee even if I tried (and I tried).

Two weeks later, my supervisor came in and said it was time to get out of the trailer and back in the field. “Thanks, but no thanks,” I said, and went back to Isla Vista, north of Santa Barbara, where I promptly talked my brother and friend into a surfing trip to Hawaii for three weeks. I needed to be in the water again.

Reflecting on a Rite of Passage

That summer in the oil fields put the finishing touches on ten years of toughening; fighting on a daily basis and the experience of horrific deaths tends to do that to a man. It was a rite of passage that I had come through. I wasn’t afraid anymore of what might happen to me because somehow I had survived the worst that I could imagine and lived. I was mobile and upright and had developed an attitude that life could take its best shot, but it wouldn’t be good enough to take me out. I owned the ground I stood on and the board I rode.

The early physical training from my father, the constant sparring of my youth, and the daily fights that broke out every time I showed up for work that summer had, for better or worse, hardened me in my approach to life. I had been hazed on a daily basis and almost gang-raped, but I had also swung a 48-inch pipe wrench in 112-degree heat that so transformed my body I looked like a body-builder. I had been face-to-face with a man burned to death and had nearly been blown to bits myself, and yet somehow I was alive. Whatever was next, bring it on, I thought; I’d already seen Hell.

This attitude manifested itself in Hawaii, where non-natives are often targets for natives looking to assert themselves on the waves. My brother, friend, and I were surfing one day when, out of the blue, a large Hawaiian guy tried to pick a fight right then and there in the water over us taking his waves. I knew his type from my time in the oil fields—he didn’t care about the waves; he just wanted to pick on someone—so I started slowly paddling to the beach, looking over my shoulder and calling back, “Come on. Let’s go so I can beat the crap out of you and we can get this over with.”

That was my voice I heard in my ears. After spending all of my life afraid of fighting—of being able to throw a good punch and wondering if I could actually take one—I was now the protector and the enforcer. After McKittrick, I wasn’t afraid of anything.

“Come on,” I yelled back again, still paddling on my board back to the beach. “Let’s go! I want to get some more surfing in.”

Floating on his board with his mouth hanging open, the guy just stared at me and started to nervously giggle. His gang backed him up, heckling like a pack of hyenas, but he did nothing. I paddled back out past the pack and their “alpha,” and as I passed, I said, “I thought so.”

My brother and friend looked surprised, but said nothing. We finished the day and the rest of our three-week trip surfing, then headed back to California.

Look for Mako’s World: A Memoir of Calculated Adventures to be published in Spring of 2022.

Fresh & Random Linkage

“Wordle Founder Josh Wardle on Going Viral and What Comes Next” - Is anybody (other than me) not playing Wordle? Just curious.

“Daniel Radcliffe To Play ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic In Upcoming Biopic” - Whatever you think of ‘Weird Al,’ you gotta admire the success of his tongue-in-cheek humor, evident in his statement on the movie being made about him. Classic.

“A Letter from Your Mother” - Simply put, this 1807 letter from Johanna Schopenhauer to her son, philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, is tough love.

Until next time.

Why Subscribe?

Why not? Second Drafts is a once-a-week newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Keep Connected

You’re welcome to follow me on Twitter.