Dear Reader,

As you may have noticed, I’ve been on a memoir kick of late, and this is one I’d recommend for a variety of reasons—subject matter, story, time period, excellence of writing—just to name a few. If you’re a fan of C.S. Lewis, you owe it to yourself to read about his early years.

As a reminder, these monthly reviews are long essays with plenty of book excerpts to get a feel for the author’s writing (and not just my musings about it). My goal is to draw out the main themes, tie them together, and share how the book impacted me and may be of interest to others.

Scroll to the bottom of this page for Peaches’ Pick as to what we’ll be reading for June. Thanks for supporting my writing here at Second Drafts. I hope you benefit from the review.

Craig

Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life by C.S. Lewis

It’s always good to remember that adults come from somewhere; that is, none of us arrives fully-formed, but each is instead a product of the nature and nurture of our parents and others who were part of our childhoods. Heck, the Bible reminds us that even Jesus required time to grow up (“And Jesus grew in wisdom and stature, and in favor with God and man.” Luke 2:52), though mercifully, God saw fit not to lead the apostles to write about Jesus’ teenage years. Which of us as teenagers would have benefitted from our parents starting a sentence with, “When Jesus was your age…?”

Thank the Maker.

I mention all this as part of my introduction to a rare gift from one of the most important Christian authors of the 20th century. C.S. Lewis wrote Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life in 1956, and in it he covers the first 25 years of his life in (mostly) pre-World War I Ireland and England, in and out of boarding schools, and with characters and crucibles of faith that formed him.

In the midst of these boyhood experiences, Lewis drops names of authors and titles of books, the quality and quantity of which make the jaw drop at how far the world has waned from what once was an education that was as inspiring as it was standard. Reading Lewis about what he was reading is gold for those who want a better understanding of how good literature can form not only good thoughts and behaviors in men, but also the facilities necessary to think and accomplish them.

Most significantly, Surprised by Joy chronicles the journey of a man who did not consider himself particularly emotional. His conversion to Christianity was remarkably rational, yet it changed everything for Lewis—including his emotional life—and will resonate with readers (especially those like myself who spend most of the time in our heads, despite having huge hearts that are often misunderstood).

As Lewis writes in the introduction:

“This book is written partly in answer to requests that I would tell how I passed from Atheism to Christianity and partly to correct one or two false notions that seem to have got about. How far the story matters to anyone but myself depends on the degree to which others have experienced what I call ‘joy.’ If it is at all common, a more detailed treatment of it than has (I believe) been attempted before may be of some use. I have been emboldened to write of it because I notice that a man seldom mentions what he had supposed to be his most idiosyncratic sensations without receiving from at least one (often more) of those present the reply, ‘What! Have you felt that too? I always thought I was the only one.’” (p. vii)

If you’ve “felt that too,” read on and learn from this humble man God has used so powerfully in the lives of so many through his writing.

Death of His Mother, Strain with His Father

Born in Belfast, Ireland, in 1898, Lewis grew up with an older brother and parents who were quite opposites, the differences shaping Lewis temperament from the start:

“From my earliest years, I was aware of the vivid contrast between my mother’s cheerful and tranquil affection and the ups and downs of my father’s emotional life, and this bred in me long before I was old enough to give it a name a certain distrust or dislike of emotion as something uncomfortable and embarrassing and even dangerous.”

Sadly, Lewis lost his mother to cancer when he was nine, an experience that had a profound impact on his young life and put strain on his relationship with his father:

“Children suffer not (I think) less than their elders, but differently. For us boys the real bereavement had happened before our mother died. We lost her gradually as she was gradually withdrawn from our life into the hands of nurses and delirium and morphia, and as our whole existence changed into something alien and menacing, as the house became full of strange smells and midnight noises and sinister whispered conversations. This had two further results, one very evil and one very good. It divided us from our father as well as our mother. They say that a shared sorrow draws people closer together; I can hardly believe that it often has that effect when those who are of widely different ages. If I may trust my own experience, the sight of adult misery and adult terror has an effect on children which is merely paralyzing and alienating. Perhaps it was our fault. Perhaps if we had been better children we might have lightened our father’s sufferings at this time. We certainly did not. His nerves had never been of the steadiest and his emotions had always been uncontrolled. Under the pressure of anxiety his temper became incalculable; he spoke wildly and acted unjustly. Thus by a peculiar cruelty of fate, during those months the unfortunate man, had he but known it, was really losing his sons as well as his wife. We were coming, my brother and I, to rely more and more exclusively on each other for all that made life bearable; to have confidence only in each other. I expect that we (or at any rate I) were already learning to lie to him. Everything that had made the house a home had failed us; everything except one another. We drew daily closer together (that was the good result)—two frightened urchins huddled for warmth in a bleak world.” (p. 18-19)

Schooling & Faith

Having been privately tutored at home up to that point, Lewis’ father enrolled him and his brother into the first of several English boarding schools they would attend during their youth. Despite a rough start and a harassing headmaster (whom they unaffectionately called “Oldie”), Lewis found himself coming to faith. He writes:

“But I have not yet mentioned the most important thing that befell me at Oldie’s There first I became an effective believer. As far as I know, the instrument was the church to which we were taken twice every Sunday. This was high “Anglo-Catholic.” On the conscious level I reacted strongly against its peculiarities—was I not an Ulster Protestant, and were not these unfamiliar rituals an essential part of the hated English atmosphere? Unconsciously, I suspect, the candles and incense, the vestments and the hymns sung on our knees, may have had a considerable, and opposite, effect on me. But I do not think they were the important thing. What really mattered was that I here heard the doctrines of Christianity (as distinct from general ‘uplift’) taught by men who obviously believed them. As I had no skepticism, the effect was to bring to life what I would already have said that I believed. (p. 33)

Lewis goes on to talk about his main motivation and accompanying responses thereto:

“I feared for my soul; especially on certain blazing moonlit nights in that curtainless dormitory—how the sound of other boys breathing in their sleep comes back! The effect, so far as I can judge, was entirely good. I began seriously to pray and to read my Bible and to attempt to obey my conscience. Religion was among the subjects which we often discussed; discussed, if my memory serve me, in an entirely healthy and profitable way, with great gravity and without hysteria, and without the shamefacedness of older boys. How I went back from this beginning you shall hear later.” (p. 34)

Their time at Oldie’s came to an end due to the school closing, and the boys transferred schools, first for a brief stint at Campbell, then to Chartres in Wyvern. It was during the weekend and holiday commutes that Lewis, age 13, discovered books:

“We made the discovery (some people never make it) that real books can be taken on a journey and that hours of golden reading can so be added to its other delights. (It is important to acquire early in life the power of reading sense wherever you happen to be. I first read Tamburlaine while traveling from Larne to Belfast in a thunderstorm, and first read Browning’s Paracelsus by a candle which went out and had to be relit whenever a big battery fired in a pit below me, which I think it did every four minutes all that nigh.) The homeward journey was even more festal. It had an invariable routine: first the supper at a restaurant—it was merely poached eggs and tea but to us the tables of the gods—then the visit to the old Empire (there were still music halls in those days)—and after that journey to the Landing Stage, the sight of great and famous ships, the departure, and once more the blessed salt on our lips.” (p. 56-57)

An Erosion of Faith

It was during his time at Chartres, however, that Lewis’ faith was less challenged and more eroded by the unlikeliest of culprits, the house matron, Miss C. Writes Lewis:

“The chronology of this disaster is a little vague, but I know for certain that it had not begun when I went there and that the process was complete very shortly after I left. I will try to set down what I know of the conscious causes and I suspect of the unconscious.

Most reluctantly, venturing no blame, and as tenderly as I would at need reveal some error in my own mother, I must begin with dear Miss C., the Matron. No school ever had a better Matron, more skilled and comforting to boys in sickness, or more cheery and companionable to boys in health. She was one of the most selfless people I have ever known. We all loved her; I, the orphan, especially. Now it so happened that Miss C., who seemed old to me, was still in her spiritual immaturity, still hunting, with the eagerness of a soul that had a touch of angelic quality in it, for a truth and a way of life. Guides were even rarer then than now. She was as I should now put it floundering in the mazes of Theosophy, Rosicrucianism, Spiritualism; the whole Anglo-American Occultist tradition. Nothing was further from her intention than to destroy my faith; she could not tell that the room into which she brought this candle was full of gunpowder. I had never heard of such things before; never, expect in a nightmare or a fairy tale, conceived of spirits other than God and men. I had loved to read of strange sights and other world and unknown modes of being, but never with the slightest belief; even the phantom dwarf had only flashed on my mind for a moment. It is a great mistake to suppose that children believe the things they imagine.” (p. 58-59)

Nevertheless, these conversations with Miss C. built on themselves, tempting Lewis with Occultism’s vagueness and drawing him away from what he had initially believed:

“And oh, the relief of it! Those moonlit nights in the dormitory at Belsen faded far away. From the tyrannous noon of revelation I passed into the cool evening of Higher Thought, where there was nothing to be obeyed, and nothing to be believed except what was either comforting or exciting. I do not mean that Miss C. did this; better say that he Enemy did this in me, taking occasion from things she innocently said.” (p. 60)

College & War

But all was not lost. Lewis discovered the music of Wagner and Norse mythology, two sources from which he records receiving “the stab of Joy” over time. He then won a scholarship to and entered Wyvern College in 1913, struggling with the school as a whole, but benefitting from teachers who guided him in his studies of the humanities in multiple languages (Latin, French, German, Italian, and English).

Transferring schools from Wyvern to Bookham in 1914, Lewis further made the acquaintances of Homer, Euripides, Sophocles, and Aeschylus; Dante and Milton also became companions, as did Samuel Johnson, George MacDonald, George Herbert, and a handful of Romantics—all against a backdrop of the start of World War I. Anticipating that the war would probably last past when Lewis reached military age,

“…I was compelled to make a decision which the law had taken out of the hands of English boys of my own age; for in Ireland we had no conscription. I did not much plume myself even then for deciding to serve, but I did feel that the decision absolved me from taking any further notice of the war…Accordingly I put the war on one side to a degree which some people will think shameful and some incredible. Others will call it a flight from reality. I maintain that it was rather a treaty with reality, the fixing of a frontier. I said to my country, in effect, ‘You shall have me on a certain date, not before. I will die in your wars if need be, but till then I shall live my own life. You may have my body, but not my mind. I will take part in battles but not read about them.’” (p. 158)

Sure enough, Lewis’ papers came through and he enlisted in the service in 1917, less than a term after starting at Oxford. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Somerset Infantry and arrived in the front line trenches on his 19th birthday (November 22, 1917). He was wounded at Mt. Bernenchon, near Lillers, in April, 1918. Of that time, Lewis writes:

“I am surprised that I did not dislike the army more. It was, of course, detestable. But the words ‘of course’ drew the sting. That is where it differed from Wyvern. One did not expect to like it. Nobody said you ought to like it. Nobody pretended to like it. Everyone you met took it for granted that the whole thing was an odious necessity, a ghastly interruption of rational life. And that made all the difference. Straight tribulation is easier to bear than tribulation which advertises itself as a pleasure. The one breeds camaraderie and even (when intense) a kind of love between the fellow sufferers; the other, mutual distrust, cynicism, concealed and fretting resentment.” (p. 188)

Lewis then became sick with “trench fever,” and during his hospital recovery discovered a volume of essays by G.K. Chesterton, of which he wrote,

“In reading Chesterton, as in reading MacDonald, I did not know what I was letting myself in for. A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading. There are traps everywhere—‘Bibles laid open, millions of surprises,’ as Herbert says, ‘fine nets and stratagems.’ God is, if I may say it, very unscrupulous.” (p. 191)

Oxford and a Heavenly Conspiracy

Lewis returned to Oxford in January 1919, where he met multiple key men who made an impact on and inspired him with “traits that I liked but found (for I was still very much a modern) oddly archaic; chivalry, honor, courtesy, ‘freedom,’ and ‘gentillesse.’” They overthrew and pummeled his chronological snobbery, causing him to “wonder if the archaic was simply the civilized, and the modern simply the barbaric.”

But it wasn’t just Lewis’ personal peers who were charming him back to the faith:

“All the books were beginning to turn against me. Indeed, I must have been as blind as a bat not to have seen, long before, the ludicrous contradiction between my theory of life and my actual experiences as a reader. George MacDonald had done more to me than any other writer; of course it was a pity had that bee in his bonnet about Christianity. He was good in spite of it. Chesterton had more sense than all the other moderns put together; bating, of course, his Christianity. Johnson was one of the few authors whom I felt I could trust utterly; curiously enough, he had the same kink. Spenser and Milton by a strange coincidence had it too. Even among ancient authors the same paradox was to be found. The most religious (Plato, Aeschylus, Virgil) were clearly those on whom I could really feed. On the other hand, those writers who did not suffer from religion and with whom in theory my sympathy ought to have been complete—Shaw and Wells and Mill and Gibbon and Voltaire—all seemed a little thin; what as boys we called ‘tinny.’ It wasn’t that I didn’t like them. They were all (especially Gibbon) entertaining; but hardly more. There seemed to be no depth in them. They were too simple. The roughness and density of life did not appear in their books.” (p. 213-214)

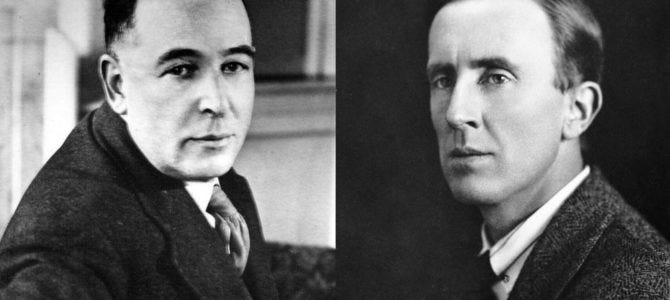

The plot continued along this same theme when Lewis became a temporary lecturer at Magdalen College, where another slew of men “enlarged my very idea of what a learned life should be.” In addition to meeting with those gentlemen, Lewis began officially teaching for the English Faculty and made two other significant friends,

“…both Christians (these queer people seemed now to pop up on every side) who were later to give me much help in getting over the last stile. They were H.V.V. Dyson (then of Reading) and J.R.R. Tolkien. Friendship with the latter marked the breakdown of two old prejudices. At my first coming into the world I had ben (implicitly) warned never to trust a Papist, and at my first coming into the English Faculty (explicitly) never to trust a philologist. Tolkien was both.” (p. 216)

Eventually, Lewis writes, he came to believe in God:

“You must picture me alone in that room in Magdalen, night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England. I did not then see what is now the most shining and obvious thing; the Divine humility which will accept a convert even on such terms. The Prodigal Son at least walked home on his own feet. But who can duly adore that Love which will open the high gates to a prodigal who is brought in kicking, struggling, resentful, and darting his eyes in every direction for a chance to escape? The words ‘compelle intrare,’ compel them to come in, have been so abused by wicked men that we shudder at them; but, properly understood, they plumb the depth of the Divine mercy. The hardness of God is kinder than the softness of men, and His compulsion is our liberation.” (p. 228-229)

From Theism to Christianity

Lewis’ conversion, of course, was to Theism, not Christianity. As he writes,

“I knew nothing yet about the Incarnation. The God to whom I surrendered was sheerly nonhuman…As soon as I became a Theist I started attending my parish church on Sundays and my college chapel on weekdays; not because I believed in Christianity, nor because I though the difference between it and simple Theism a small one, but because I thought one ought to ‘fly one’s flag’ by some unmistakable overt sign. I was acting in obedience to a (perhaps mistaken) sense of honor. The idea of churchmanship was to me wholly unattractive. I was not in the least anticlerical, but I was deeply antiecclesiastical.” (p. 230, 233-234)

Lewis’ final transition to Christian faith is perhaps as underwhelming as any in the course of history, and yet has since produced a harvest of righteousness for so many in its fruits. The climax (if one could call it that) of the story:

“As I drew near the conclusion, I felt a resistance almost as strong as my previous resistance to Theism. As strong, but shorter-lived, for I understood it better. Every step I had taken, from the Absolute to ‘Spirit’ and from ‘Spirit’ to ‘God,’ had been a step toward the more concrete, the more imminent, the more compulsive. At each step one had less chance ‘to call one’s soul one’s own.’ To accept the Incarnation was a further step in the same direction. It brings God nearer, or near in a new way. And this, I found, was something I had not wanted. But to recognize the ground for my evasion was of course to recognize both its shame and its futility. I know very well when, but hardly how, the final step was taken. I was driven to Whipsnade [Zoo] one sunny morning. When we set out I did not believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and when we reached the zoo I did.”

The Joy That Surprises

In the end, the Joy that surprised Lewis was the Joy that was a means, not an end:

“There was no doubt that Joy was a desire (and, in so far as it was also simultaneously a good, it was also a kind of love). But a desire is turned not to itself but to its object. Not only that, but it owes all its character to its object…Joy itself, considered simply as an event in my own mind, turned out to be of no value at all. All the value lay in that of which Joy was the desiring.” (p. 220)

Lewis closes the book with an insightful illustration of his point:

“When we are lost in the woods the sight of a signpost is a great matter. He who first sees it cries, ‘Look!’ The whole party gathers round and stares. But when we have found the road and are passing signpost every few miles, we shall not stop and stare. They will encourage us and we shall be grateful to the authority that set them up.’” (p. 238)

In His grace, God used people and books and music to serve as signposts of surprising Joy that guided Lewis to and on the road of salvation; there was no dramatic conversion, but simply a removal of the scales from the eyes of Lewis’ heart and mind to see and embrace the gift of grace offered in the person of Christ. Nothing in Lewis’ childhood or boyhood was wasted as part of God’s pursuit, and Lewis’ story is a powerful reminder of God’s action and sovereignty in the lives of His children, as well as our need to be surprised by that same kind of Joy and trust the God who gives it.

June Peaches’ Pick: Still Time to Care by Greg Johnson

I’ve written about my friend and former pastor Greg Johnson before, and it’s past due that I read his new (December 2021) book, Still Time to Care: What We Can Learn from the Church’s Failed Attempt to Cure Homosexuality. From the back cover:

“At the start of the gay rights movement in 1969, evangelicalism's leading voices cast a vision for gay people who turn to Jesus. It was C.S. Lewis, Billy Graham, Francis Schaeffer, and John Stott who were among the most respected leaders within theologically orthodox Protestantism. We see with them a positive pastoral approach toward gay people, an approach that viewed homosexuality as a fallen condition experienced by some Christians who needed care more than cure.

With the birth and rise of the ex-gay movement, the focus shifted from care to cure. As a result, there are an estimated 700,000 people alive today who underwent conversion therapy in the United States alone. Many of these patients were treated by faith-based, testimony-driven parachurch ministries centered on the ex-gay script. Despite the best of intentions, the movement ended with very troubling results. Yet the ex-gay movement died not because it had the wrong sex ethic. It died because it was founded on a practice that diminished the beauty of the gospel.

Yet even after the closure of the ex-gay umbrella organization Exodus International in 2013, the ex-gay script continues to walk about as the undead among us, pressuring people like me to say, ‘I used to be gay, but I'm not gay anymore. Now I'm just same-sex attracted.’

For orthodox Christians, the way forward is a path back to where we were forty years ago. It is time again to focus with our Neo-Evangelical fathers on care—not cure—for our non-straight sisters and brothers who are living lives of costly obedience to Jesus.

With warmth and humor as well as original research, Still Time to Care will chart the path forward for our churches and ministries in providing care. It will provide guidance for the gay person who hears the gospel and finds themselves smitten by the life-giving call of Jesus. Woven throughout the book will be Richard Lovelace’s 1978 call for a ‘double repentance’ in which gay Christians repent of their homosexual sins and the church repents of its homophobia—putting on display for all the power of the gospel.”

Pick up a copy and read along with us! Book review to be published Saturday, June 25.