Dear Readers,

This is a special Father’s Day edition of Second Drafts. I’ll return to news and culture commentary in another week, but I wanted to share this meditation from the end of this first Father’s Day without my Dad. Thanks (as always) for reading.

Happy Father’s Day,

Craig

“A competent farmer is his own boss. He has learned the disciplines necessary to go ahead on his own, as required by economic obligation, loyalty to his place, pride in his work. His workdays require the use of long experience and practiced judgment, for the failures of which he knows that he will suffer.

The best farming requires a farmer—a husbandman, a nurturer—not a technician or businessman. A good farmer, on the other hand, is a cultural product; he is made by a sort of training, certainly, in what his time imposes or demands, but he is also made by generations of experience. This essential experience can only be accumulated, tested, preserved, handed down in settled households, friendship, and communities that are deliberately and carefully native to their own ground, in which the past prepared the present and the present safeguards the future.”

—from The Unsettling of America by Wendell Berry (pp. 48-49)

“Couldn't curse, couldn't cry, couldn't crawl

Threw my hands up in the face of it all

So, this is what it's like to be the child

of a man who's dead and gone”

—from “My Father’s Crown” by Charlie Peacock

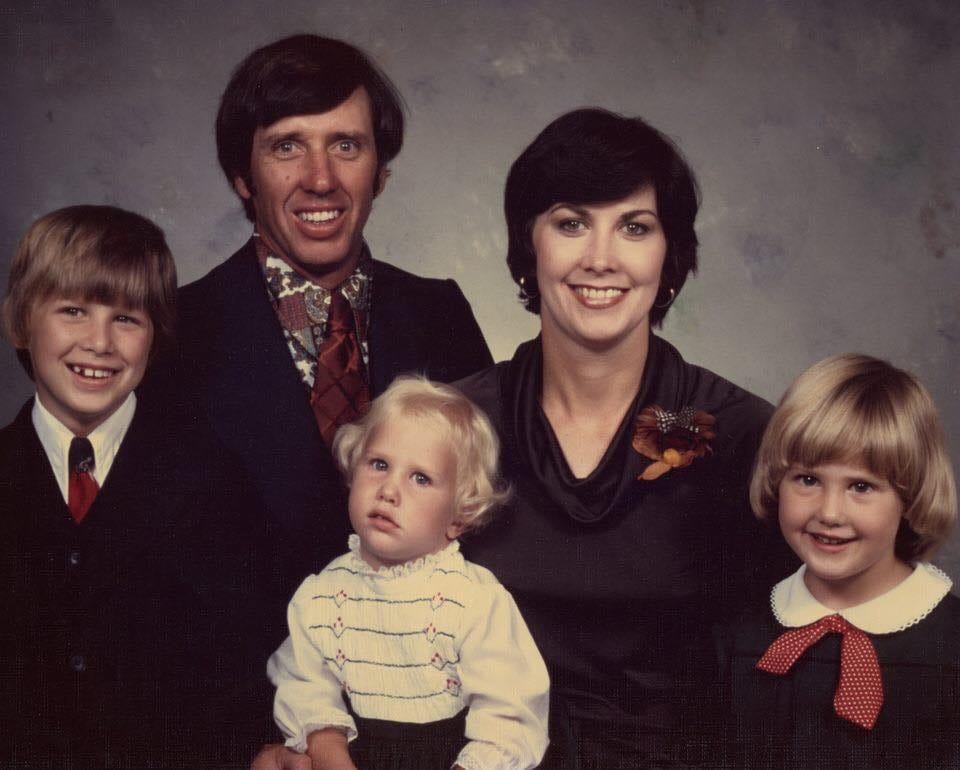

Today was Father's Day, and for the first time in my 54 years, it was a day without my father, Roger, being available for a Sunday afternoon Father’s Day call. Dad passed away on February 13, just a few weeks after celebrating 60 years of marriage to my mother, Charlotte. At 82, he lived a full life, one rooted deeply in the Pike County soil he cherished, and one that, in its later years, blossomed in faith.

I’ve been thinking about what it means to be a “farmer” and a “good farmer.” Wendell Berry, in his profound reflections, speaks of a farmer as a "husbandman, a nurturer," not just a technician or businessman. This description perfectly encapsulates my father and the long line of Dunhams before him, as their lives were measured not by the clock, but “by the task and his endurance; they last as long as necessary or as long as he can work.”

In the four months since Dad’s death, my mother, two sisters, and two brothers-in-law have more strongly linked arms with Megan and me (not to mention plenty of extended family and friends in Pike County), to work the custom farming plan Dad already had in place in his “didn’t want to bother anyone about it” way. It’s gone well, the crops are up, and we’re all still speaking to—and even enjoying!—each other in a new and different way. I’m very grateful for this.

But on this first Father's Day without Dad, I also find myself thinking about what it means to be a “cultural product”—as Berry describes—and what happens when the culture that produced you begins to end with you.

Six Generations & the Last of the Line

Emily, my first grandchild, represents the sixth generation of our family I have known or can remember. Though I barely recall my Great-Grandmother Rachel, I still have her Bible, marked up with her early 20th-century Women's Christian Temperance Union notes. She was the oldest generation for me—the first personal link in a chain I can trace.

The generations cascade from there: my grandparents Dean and Carolyn (along with Raymond and Helen on the Richardson side); my parents, Roger and Charlotte; my sisters, Jamie and Jill; my four daughters—Maddie, Chloe, Katie, and Millie; and now Emily, born sixteen months ago into the same month she would lose her great-grandfather one year later.

Though I have uniquely been involved with all six of these generations, it’s difficult to describe how helpless I feel to bridge the gaps between them. Time and distance create chasms that love alone cannot span. Dad only got to meet Emily once, at Thanksgiving—a fact that leaves me glad, but also very sad. Unlike my first vague (but clear) memory of Great-Grandmother Rachel and our game of catch, Emily, barely one-year-old last Thanksgiving, is left with little but a photo.

When Emily was born, I jokingly texted Mom that I needed Dad to “sign over the copyright to ‘Grandpa Dunham,’ since he's now officially upgraded to ‘Great-Grandpa.’” Mom texted back that he was happy to do that—and he was. But upon reflection, I confess I may not have been ready for what that transfer really meant.

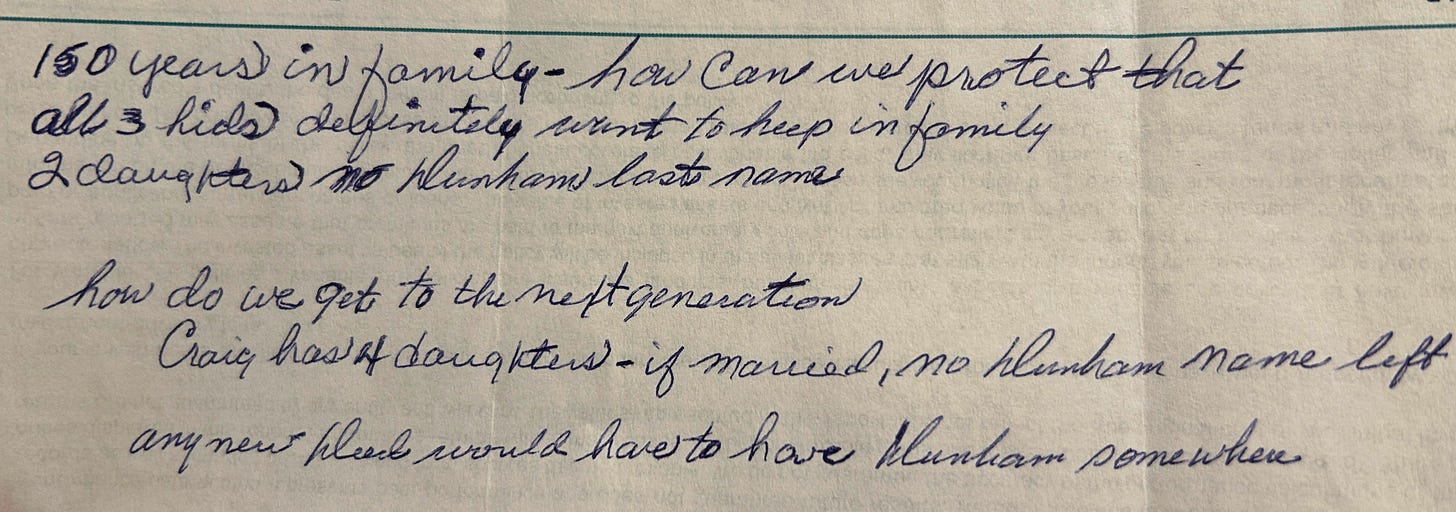

It's true that to Emily, as well as however many or few grandchildren God may grant us, I will be known as “Grandpa Dunham.” But even if, twenty-five years down the road, I get “graduated” to “Great-Grandpa,” it will not be to make room for a new “Grandpa Dunham.” It might be a Grandpa Clark, Grandpa Crase, or Grandpa Leong—the surnames my first three daughters have taken in marriage—but not a new “Grandpa Dunham.”

I’m the last male of our Dunham line, so the title dies with me.

Believe it or not, this reality has haunted me since I was eight years old and I learned that my parents weren’t planning to have more children beyond my two younger sisters. While I had no real qualms about being the only boy, even then, long before death had come for Dean—the original “Grandpa Dunham” I knew and loved—I remember feeling some security in knowing there were still two generations of Dunham men between death and me. Though I’d lived long enough in a rural community to learn death didn’t always follow chronological lines, there was at least some (false) security in this possibility.

By God's grace, Dunham grandfathers have lived long lives of honor and dignity—“No scoundrels,” my Grandmother Carolyn would famously say (though she spoke, of course, before my time). I just wish, for the sake of their memory, my appropriation of the title of “Grandpa Dunham” didn’t have to be the final one.

The Grace That Changes Everything

My father was a man of the earth and the fifth generation to farm the land our family has owned and labored on since 1855—land that is recognized as an Illinois Department of Agriculture Sesquicentennial Farm. Dad was named Illinois' Soil and Water Conservation Farmer of the Year in 1993, served on Governor Jim Edgar's State Soil and Water Conservation Advisory Board.

But Dad’s legacy stretched beyond the fields. He was a pillar in the Pike County community—a steadfast presence in the Griggsville American Legion and on school consolidation committees; a fire district treasurer and a township trustee; and for many years, the quiet, consistent scorekeeper for the Griggsville Junior High Eagles boys basketball team. These were the public markers of a man who understood obligation, community, and the dignity of work.

However, as much as he was known for his agricultural prowess and civic dedication, it’s the quiet transformation of Dad’s later years that resonates most profoundly with me now.

In July 1988, during one of the drought summers Dad would later remember as among Pike County’s worst, he and I sat on the back patio “listening to the corn grow.” Having been a Christian for three years, I had determined to share the Gospel with my father. As Dad was always willing to do, he listened as I spoke of man’s need for God’s forgiveness through Christ’s sacrifice. At the end of my appeal, he thought silently for a minute, looked over the field south of the house, then turned back to me and simply said, “I’m not interested in that right now.”

It wasn’t a rejection, just a statement of his present state of mind and soul. We never spoke of the matter again. I went to college, moved west, married, and raised four daughters. Dad continued to farm, and life carried on.

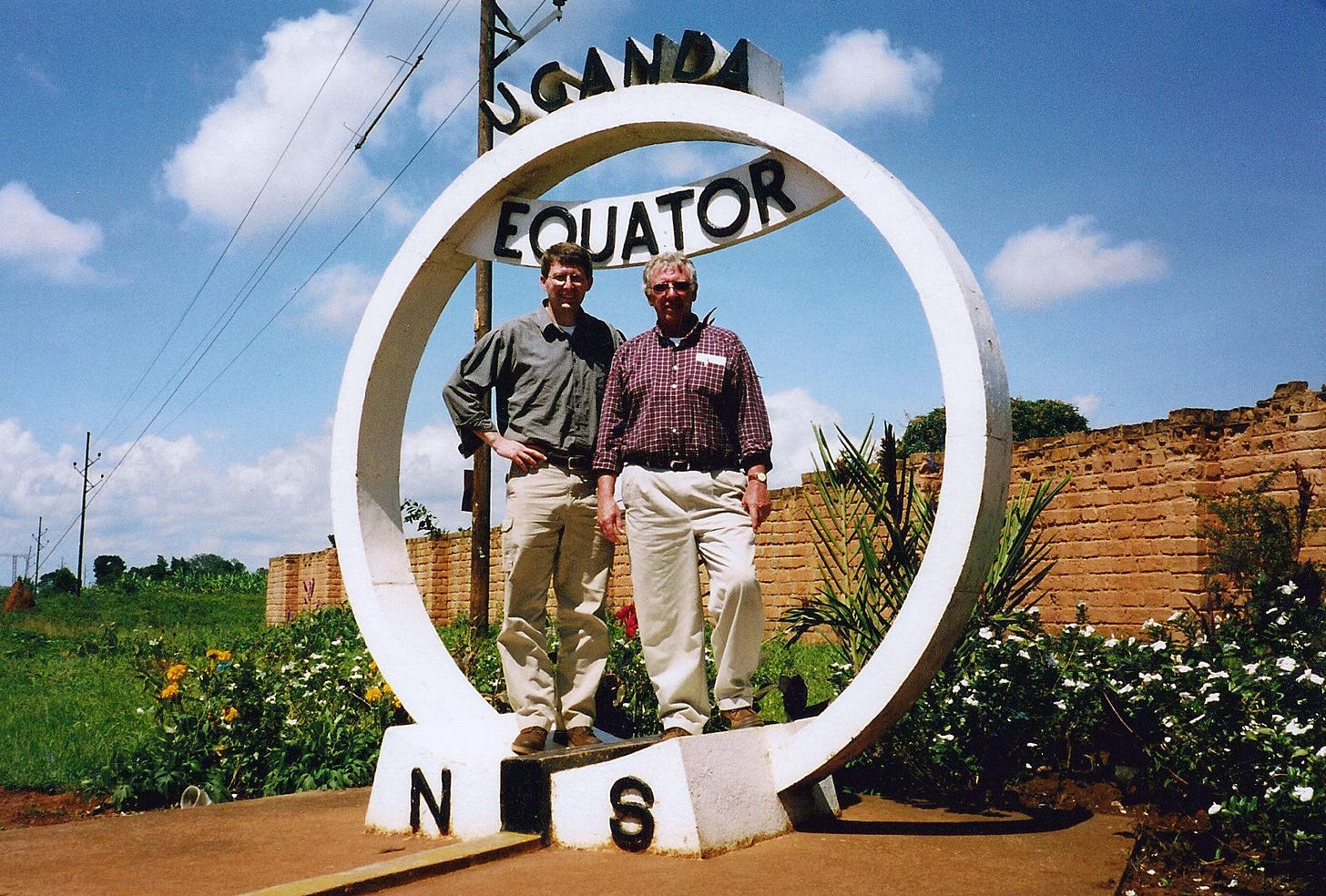

Years later, in 2001 and 2004, I made two different trips to the African country of Uganda as Megan and I had been considering possible overseas work at a Christian college that was starting up. While I was making plans for trip number two, Dad called and, after the usual initial conversation about the weather, said he wanted to make the trip with me. Months later, we did.

Something had shifted. As Mom and Dad found a home at First Christian Church, I believe Dad’s growing faith was what led him to asking if he could join me on my second trip, a trip that revealed even more of his burgeoning spiritual curiosity. In years to come, Dad would talk about sermons, about other men in the congregation he admired, even about reading the Bible—a children’s Bible, he confessed, because it helped him understand. He found wisdom in Proverbs and Psalms and appreciated the practical teachings of James, though he admitted Paul’s “lofty language” wasn’t quite for him.

Dad's reputation in the community had always been good, but it began to morph a bit—not because he became more successful as a farmer, but because grace was working its way out in his life. Jason, who worked Saturdays for Dad for years, remembered making a mistake with tractor maintenance. Dad’s response? “I guess I'll go to John Deere to get more oil.” No anger, no frustration—just a merciful grace Dad had come to know in Jesus. That hadn’t always been his way.

This grace transformed my father from a proud and sometimes stubborn man into the softer and humbler man all of us—wife, children, grandchildren, church members, neighbors—dearly loved. Through regeneration, repentance, and redemption, the Lord had converted Dad from being a flawed sinner to a forgiven saint. What began with “I’m not interested” had culminated in full surrender.

The Final Weeks

The rapid decline of Dad’s health, from Thanksgiving to his passing in February, was jarring. My sisters and I worried about how Dad would handle being dependent on others after a lifetime of fierce independence. What we experienced in those final weeks, however, was the most vulnerable version of Dad any of us had known. He thanked us for caring for him, never complained about his situation, never questioned God about his plight. Instead, he marveled with us at how God had graciously spared him the pain normally associated with stage four cancer.

At his visitation, someone described Dad as “chasing after Jesus.” But I corrected them: my father never chased after anything—it took him six months to ask my mother out after they first met, and his marriage proposal was as unromantic of a proposal as they come: “Charlotte, I think we can make this work.” No, Dad didn't chase after Jesus. It was Jesus—the great “Hound of Heaven,” the Good Shepherd who left the ninety-nine to go after the one—who chased after him. And once God’s grace is on your heels, it's only a matter of time before He gets His man.

Living Between Memory and Hope

So here I am at the end of this first Father’s Day without Dad, feeling the weight of being the last “Grandpa Dunham” and trying to make sense of what that inheritance means. I am, as Berry describes, a “cultural product” of generations past, in moniker the last of our particular Dunham line. And that feels…significant (though I'm not sure all that it means).

In the grand scheme of things, while our branch of the Dunham name may indeed end with me, the essential experience—character formed by faith and values rooted in service to others; the understanding that we are stewards of more than just land—these things continue in new forms, in new names, and in the lives of my daughters and granddaughter who (I pray) will carry forward what matters.

Dad's death on February 13 marked the end of something, but not everything. When death comes for me as the last “Grandpa Dunham,” by God’s grace, I will trust that the land will be farmed, lessons will be taught and learned, and love will continue to be shared. After all, the cultural product that was Roger Dunham, shaped by generations of experience and ultimately transformed by grace, lives on not in the perpetuation of a family name but in the preservation of what made that name worth bearing in the first place. In that continuity—not of surname but of substance—I find peace at the end of this Father’s Day.

Thanks be to God for fathers who show, tell, and point the way home by their lives well-lived. May this be the legacy of the last “Grandpa Dunham” as well.

“O God, from my youth you have taught me,

and I still proclaim your wondrous deeds.

So even to old age and gray hairs,

O God, do not forsake me,

until I proclaim your might to another generation,

your power to all those to come.”

—Psalm 71:17-18 (ESV)

In memory of Roger Kyle Dunham (1942-2025)—faithful farmer, devoted husband, loving father, and follower of Jesus.

Beautiful, profound, and important, Craig. I loved reading this.

Im taking a pause and then a deep sigh at the beauty of your reflection of your dad. This was a beautiful tribute to your Dad, the Dunham legacy, and most of all,

to our God, the Father of us all. Thank you for this. ♥️