Grade Expectations | Marital Fidelity [Still] Matters | Chick-fil-A Making Lemonade Out of Lemons (Literally)

Plus: Don't Forget to Vote for Your Most Appreciated Story at the End

There’s plenty of news I didn’t include in this edition of Second Drafts: the Los Angeles fires are still burning (as is the blame game concerning them); the Senate confirmation hearings are their usual Circus Maximus (complete with never-ending arrival of spotlight-seeking Senators from the clown car); and Donald Trump continues to talk of acquiring Greenland as a territory (which makes strategic sense on a variety of levels, but as is typical, his rhetoric is problematic).

With the links above and your own media intake, I’ll let you track down those higher profile stories. Below are three I found more interesting. Sources and articles for this edition of Second Drafts include:

New York Times: No, you don’t get an A for effort

Graphs About Religion: Have views of marital fidelity changed over time?

Bloomberg: Chick-fil-A making lemonade out of lemons (literally)

Comments are open after each article if you’d like to engage and share your own thoughts. The more, the merrier, but be warned: they’re public, so be reasonable.

As always, thanks for reading Second Drafts,

Craig

PS: In case you missed it last weekend, I published my review of Rod Dreher’s latest book, Living in Wonder: Finding Mystery and Meaning in a Secular Age. My good friend Mitchell sent me a photo 24 hours later of him with his new copy, ordered Saturday morning and delivered Sunday afternoon. Honored by his trust.

New York Times: No, you don’t get an A for effort

Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, recently wrote this opinion piece for the New York Times about a scenario that will be familiar to every teacher worthy of the title.

“After 20 years of teaching, I thought I’d heard every argument in the book from students who wanted a better grade. But recently, at the end of a week-long course with a light workload, multiple students had a new complaint: ‘My grade doesn’t reflect the effort I put into this course.’”

What Grant is describing is not grade inflation, but grade expectation—students expecting top grades for effort, regardless of whether their work is quality. It’s the academic version of our out-of-control tipping culture in which employees in a range of fields (no longer just food service) expect extra tips for…doing their jobs.

Grant continues:

“High marks are for excellence, not grit. In the past, students understood that hard work was not sufficient; an A required great work. Yet today, many students expect to be rewarded for the quantity of their effort rather than the quality of their knowledge. In surveys, two-thirds of college students say that ‘trying hard’ should be a factor in their grades, and a third think they should get at least a B just for showing up at (most) classes.”

A B just for showing up? Is this “participation trophy” culture all over again?

No, says Grant. Whereas the “participation trophy” mentality of Millennials may have been getting something just for showing up, Generation Z’s version may be getting something just for showing effort. The two are not the same (though neither are helpful), and both are a result of misguided parenting. Writes Grant:

“The problem is that we’ve taken the practice of celebrating industriousness too far. We’ve gone from commending effort to treating it as an end in itself. We’ve taught a generation of kids that their worth is defined primarily by their work ethic. We’ve failed to remind them that working hard doesn’t guarantee doing a good job (let alone being a good person).”

Or, as Grandpa Art reminded us in 1989’s National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation,

As a former teacher and “education administrator” (a title I always loathed), neither emphasis is enough in and of itself, but even Grant’s solution is flawed in its capitulation to the modern pragmatist perspective on education:

“I make it clear that my goal is to give as many A’s as possible. But they’re not granted for effort itself; they’re earned through mastery of the material. The true measure of learning is not the time and energy you put in. It’s the knowledge and skills you take out.”

Mastery of material is inadequate without mastery of oneself. Want real work ethic and actual results? Focus on character formation instead of skills training; then encourage students to identify problems to solve instead of passions to pursue.

Better grades and outcomes will follow.

Graphs About Religion: Have views of marital fidelity changed over time?

Dr. Ryan Burge is an associate professor (beginning in August 2023) of political science at Eastern Illinois University. 60 Minutes called him, “One of the country’s leading data analysts on religion and politics.” And while his Substack newsletter, Graphs About Religion, has the least creative title in the history of least creative titles, it contains plenty of interesting data and research that goes well beyond the walls of the Church.

What makes Burge uniquely qualified for religious number-crunching? In addition to his research, he served as a pastor in the American Baptist Church for over twenty years, leading First Baptist Church of Mount Vernon, IL, for 17.5 years until its closure in July 2024. As Burge wrote, “I researched the decline of organized religion while having a front-row view of the change in my own life.”

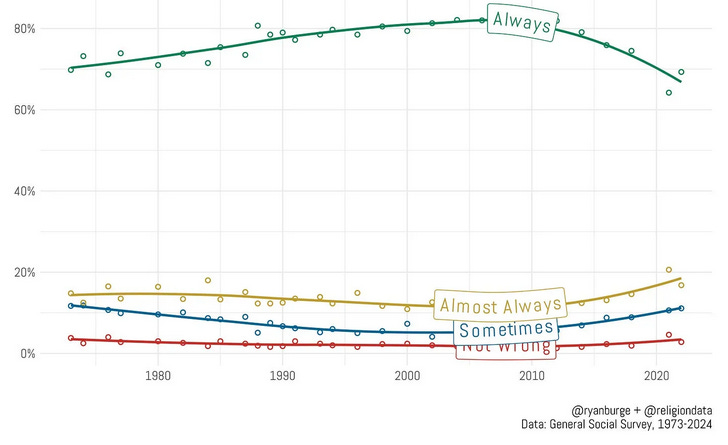

In Burge’s January 2 post, he asked the question, “Have views of marital fidelity changed over time?” His conclusions to this and several other questions having to do with marriage and people’s perspective are intriguing. He writes,

“Since 1973, the General Social Survey has been asking:

’What is your opinion about a married person having sexual relations with someone other than the marriage partner—is it always wrong, almost always wrong, wrong only sometimes, or not wrong at all?’”

Here’s what Burge tracked:

While there are no dramatic swings in public opinion, Burge observed that,

“In 1973, about 70% of Americans believed that sex with someone other than the marriage partner was ‘always’ wrong. The share slowly crept up over the decades and it reached its apex around 2010, when over 80% of folks chose this option.”

80% is not an insignificant number, but 20% of Americans are fine with infidelity? Not quite. Burge continues:

Given that between 70% and 80% of folks believed that marital infidelity was always wrong, the other three response options have never really been that popular. These lines are almost straight from the early 1970s through 2010. The most noticeable shift is the “sometimes wrong” line which started at 11% in 1973 and declined to about 5% in the early 2000s. But that has rebounded and is now back to where it started. The proportion of Americans who believe that infidelity is ‘not wrong’ has never been that large—averaging around 2% of the survey in many years.”

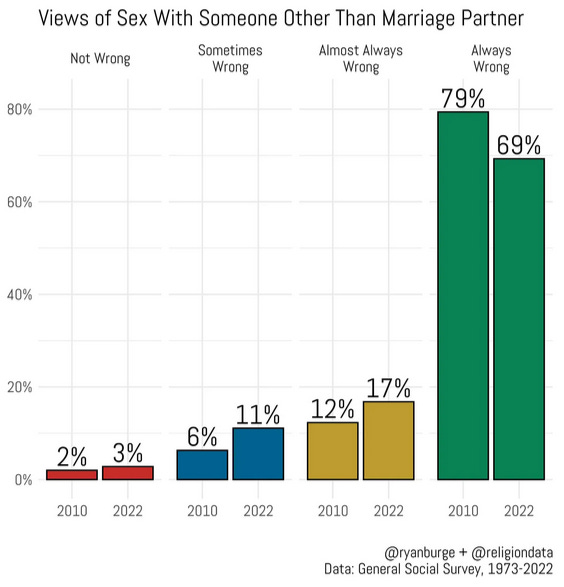

Wanting to dive a little deeper into the 2010 data, Burge created a graph of the responses to the same survey question in both 2010 and 2022:

The results? Even though there was a subtle redistribution of numbers in the 12 years represented, evenly distributed between “almost always wrong” (12% to 17%) and “sometimes wrong” (6% to 11%), the share of adults who have no issue at all with infidelity is incredibly marginal—just 3% in the 2022 data. His conclusion?

“There’s no data evidence that a lot of Americans take a Free Love approach to the topic.”

On the contrary, what the data shows is a vast majority of Americans still believe marital fidelity matters. We in the Church just need to model/help do it better.

Bloomberg: Chick-fil-A making lemonade out of lemons (literally)

Walk into any Chick-fil-A restaurant in the country (or the ones in airports and whatever malls remain) and you’ll notice two things: 1) it’s always busy (except Sundays); and 2) you’ll always find an employee waiting (and willing) to help.

That’s because Chick-fil-A (“home of the Lord’s chicken,” as my fourth-born fondly says) does as good a job as any fast-food restaurant at keeping employees present with customers by improving logistics necessary to make both happy.

Exhibit A: Chick-fil-A’s new lemon-squeezing automation, as featured in this behind-the-scenes profile in Bloomberg.

“In a plant north of Los Angeles, machines now squeeze as many as 1.6 million pounds of the fruit with hardly any human help. The facility, larger than the average Costco store at roughly 190,000 square feet, then ships bags of juice to Chick-fil-A locations, where workers add water and sugar to whip up the chain’s trademark lemonade.

The automated plant frees up in-store staff to serve customers faster, according to the company. Squeezing lemons was a tedious task that added up to 10,000 hours of work a day across all locations and resulted in many injured fingers. Removing the chore aims to make working at Chick-fil-A more appealing—key for a company looking to add hundreds of new locations while contending with a fast-food labor crunch.”

This is a great example of systems thinking that solves people challenges:

“‘You start doing the math, and there’s not going to be enough team members,’ Mike Hazelton, Chick-fil-A’s vice president of supply chain procurement and operations, said during a recent visit to the California plant.

The lemonade factory shows how restaurants are using automation to improve efficiency and wring more sales out of their stores as competition intensifies for diners and labor. Nearly half of quick-service chains say they’re understaffed, according to polling by the National Restaurant Association. The shortage is expected to persist for years.”

The difference here is Chick-fil-A is implementing automation behind the scenes rather than replacing people behind the counters. I think of this when I walk into a McDonald’s that is hoping you’ll use their new order kiosk instead of an employee to take your order. Or when I go to Walmart and the only checkout lanes available are the ones in which I become the employee (though “volunteer” is more accurate; I’m still waiting for my “employee-of-the-month” award).

As talk of the potential uses of artificial intelligence increases, the companies that leverage AI’s benefits for tedious tasks while holding onto the importance of human connection are going to experience improved business and efficiency, and ultimately be the ones to whom employees and customers become more loyal.

“Self-justification is a verbal device for restoring the appearance of rightness without doing anything about the substance.” Eugene Peterson in Tell It Slant: A Conversation on the Language of Jesus in His Stories and Prayers