The Logic of Ditching Broken Institutions | Why It’s So Hard to Live Up to Your Idea of a “Good Person" | New Literary Prize Inspires Students to Write Next "Great American Novel"

Just When You Thought It Was Safe to Go Back to Your Inbox

If you love reading about logic, human nature, and literature as I do, you’ll love this first April edition of Second Drafts. Sources and articles for this issue include:

Aaron Renn: The Logic of Ditching Broken Institutions

NPR: Why It’s So Hard to Live Up to Your Idea of a “Good Person”

The College Fix: New Literary Prize Inspires Students to Write Next “Great American Novel”

If these articles aren’t your cup of tea, leave a link or two to ones you’d like considered for future editions. I’m easy like Sunday morning.

Thanks for reading Second Drafts,

Craig

PS: I bought a new-to-me old desk! This is where the magic happens/is attempted.

Aaron Renn: The Logic of Ditching Broken Institutions

Aaron Renn is an author and Substacker I follow who writes on “domains, forces and trends shaping today’s world.” The title of yesterday’s post caught my eye, and his perspective on President Trump’s method/madness involving our American institutions is helpful. Renn writes:

“On the one hand, we need institutions badly. On the other, our institutions are functioning poorly, and most of us have no ability to affect them.”

He then presents four models of institutional engagement, with “institutional performance” on one axis, and “ability to influence an institution” on the other. This leads to four separate strategies: Defend, Participate, Reform, and Exit.

Renn then explains the gist of his argument, namely that,

“Realistically, most people have very little ability to influence the bulk of the institutions in their lives. And I think there’s a widely shared belief that many of our institutions have serious problems. How many fall into that category, which ones they are, and for what reasons are all subjects of debate. But people seem to agree that we have a problem.

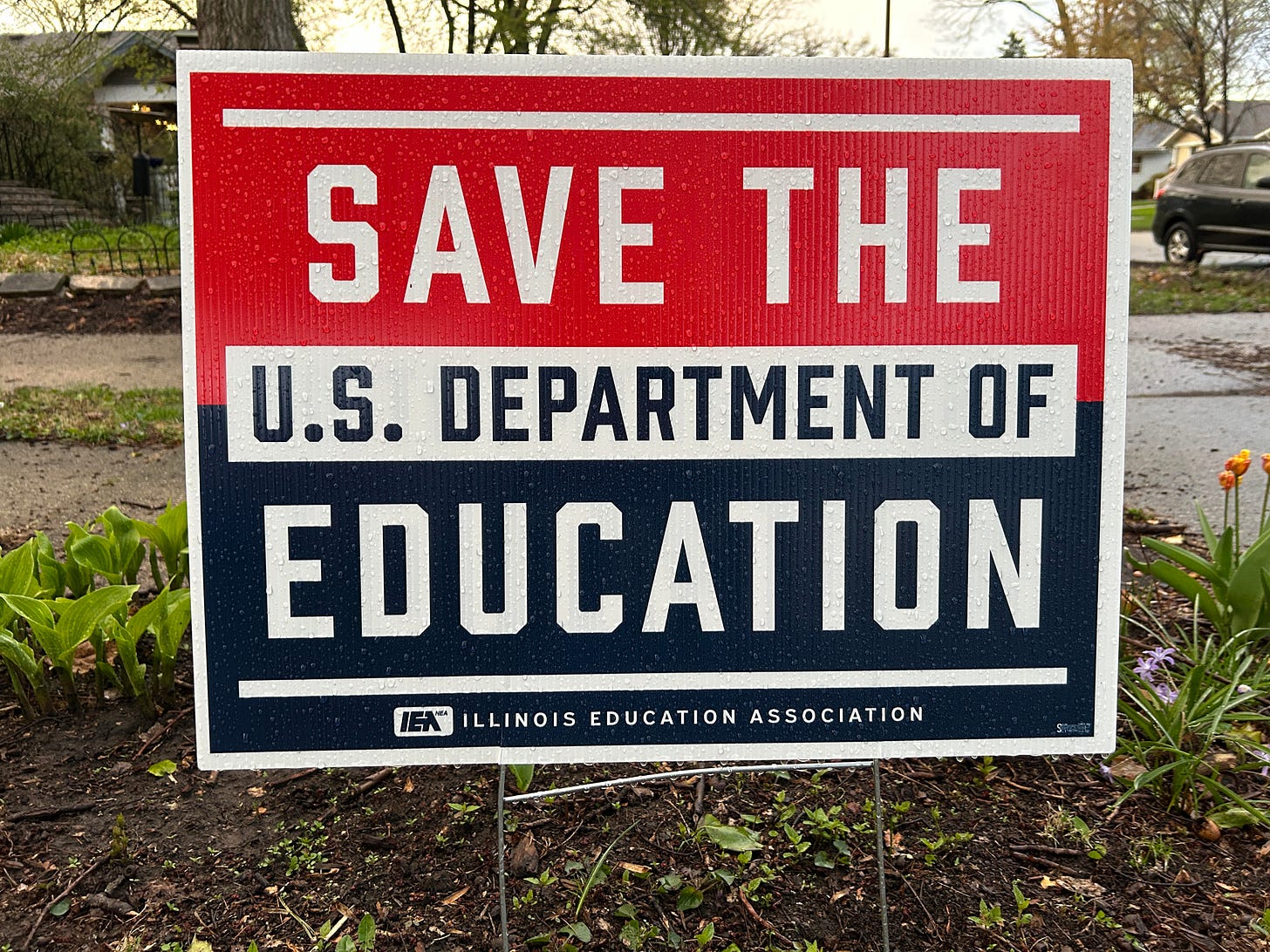

For most people in a large share of cases, the rational move is Exit. This goes along with Albert Hirschman’s (author of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty) observation that Exit has a privileged position in American culture. We see Exit in the case of public schools. Many people have abandoned them in favor of home schooling or private schooling.

So we’re in a scenario where we need institutions, but the only logical move for most people is to turn their backs on them.”

He continues discussing public schools:

“Poorly performing urban districts have proven stubbornly resistant to reform, even though there are elected officials who theoretically control the schools and are very motivated to improve them.

So what the bipartisan education reform movement did was to start supporting charter schools. They used their influence in order to build exit ramps out of the mainstream public schools into an alternative institution set. In Republican states this has gone even further with the ‘fund students not systems’ model in which families can take their state education funds to private schools as well.1 Both Democrats and Republicans have been using their influence over educational institutions to incrementally dismantle them

I’m not sure I fully buy that last sentence (show me a Democrat actively working to incrementally dismantle our abysmal educational bureaucracy), but I’ll let it go. Instead, consider the recent bureaucratic push back against the discovery of corruption and bloated spending at so many government agencies. Renn writes,

“In the case of the Trump administration and DOGE, he faces a federal bureaucracy staffed almost entirely by Democrats and which is implacably hostile to his agenda. This is not an auspicious environment for reform. It doesn’t seem very likely that the bureaucrats are going to start marching to a different tune just because the politically appointed leadership tells them to. It’s much more likely that they would use every tool in their arsenal to actively resist or delay. In this sort of environment, there’s strategic logic to the idea of using institutional influence to simply terminate or downsize the institution in question.”

One may not like the Democrats’ “resistance at all costs” position, nor Trump’s “break it and rebuild it” approach, but Renn’s is the best explanation I’ve read of the deeper “why?” behind the actions on both sides of the aisle. Apply Renn’s four-quadrant model to any aspect of the federal (or state) government and the Democrats’ message-less digging in of their heels and Trump’s ready-fire-aim gambles make sense; the rub is we the people are caught in the middle.

“Undoubtedly this strategy throws away a lot of good with the bad. But that’s a reason why leaders shouldn’t allow their institutions to become subverted or politicized. If you’re the one who planted the tares in the first place, then you’re not in a position to complain when a lot of wheat gets thrown out along with them.”

In the understatement of the year, it will be interesting to see where this goes.

NPR: Why It’s So Hard to Live Up to Your Idea of a “Good Person”

I caught part of this NPR interview last week and looked up the accompanying article. As the old saying goes, “Admitting you have a problem is the first step”; the second step is making sure the admitted problem is the actual problem.

“Psychologist and New York University business school professor Dolly Chugh has spent years studying morality and how ‘good’ people see themselves.

‘Many of us have what psychologists call a central moral identity. We care about whether we’re seen as a good person…and whether we feel like good people,’ Chugh told NPR’s Manoush Zomorodi.

But every individual has a different definition of what ‘good’ is.

‘What I'm interested in…is the gap between your definition of what a good person is and your ability to actually show up as that person,’ says Chugh.”

Whether we are seen as or feel we are good people may be a presenting symptom, but the root cause of humanity’s moral discrepancy is depravity. Chugh’s a priori presumption that we begin “good”—and can become more so in order to bridge any “gap” between definition and ability—is our real problem.

The Bible has much to say about presumed “goodness,” not the least of which are Jesus’ words in Mark 10:18 when he says, “No one is good except God alone.” The idea that we are born “good” or (at worst, “neutral”) is the biggest lie latched onto to soothe the ache that Romans 3:11-12 describes:

“None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one.”

The Bible makes no bones about our inherent goodness (or lack thereof), but Chugh does what humans tend to do when failing to meet a standard: she lowers the bar.

“Chugh says that to become better people, we need to let go of the idea of being a good person. Instead, she says to aspire to a different standard—of being a ‘good-ish’ person. A good-ish person still makes mistakes but learns from them more frequently.

‘As a good-ish person, in fact, I become better at noticing my own mistakes. I don't wait for people to point them out,’ Chugh said in a TED Talk in 2018. It's an uncomfortable, embarrassing feeling, she acknowledged. ‘But through all that vulnerability…we see progress. We see growth. We allow ourselves to get better.’”

Moving the goalposts from “good” to “good-ish,” Chugh suggests that if we will just get out of our own way, improvement will naturally and inevitably happen. But this perspective misses the truth that sin—what the Westminster Shorter Catechism defines as “any want of conformity unto, or transgression of, the law of God”—is not merely what we do; it is part of us, unable to be improved or put away. As artist Charlie Peacock sang in his 1996 song, “That’s the Point,”

“It's a point that’s missed by more than a few

Young and old, tried and true

Sin is a cancer, not just a thing you do from time to time

Like slipping or tripping or losing your keys

It’s in you, mister; sister, it’s in me”

Becoming a truly “good person” begins by agreeing with God that we’re not and could never be apart from Christ’s salvation (Romans 3:23-25). The rest of life, then, is working out that salvation with fear and trembling, “for it is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Philippians 2:12-13).

Don’t believe the lie. God’s good is way better than our “good-ish” ways can ever be.

The College Fix: New Literary Prize Inspires Students to Write Next “Great American Novel"

In case you missed it, 2025 is the 100th year anniversary of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, one of my favorite Great American Novels. (Note: If you have a moment, click over to Karen Swallow Prior’s thoughtful new essay on the book.)

While my younger self once entertained the thought of writing said Great American Novel, I have my doubts whether such a thing can even be written in the 21st century. Is there enough of an America in common to write about anymore? (Mind you, I’m not even asking if it has to be great…or even good.)

Apparently someone still thinks there is. From The College Fix:

“A new novel-writing competition with the theme ‘America 2076’ hopes to inspire new talent, particularly students, to write the next great American work of fiction.

The winning novelist at Ark Press, a new genre fiction publishing company, will receive a prize of $10,000 and have their book published on July 4, 2026. According to editor-in-chief Tony Daniel, that puts it in the top five biggest prizes in America for unpublished fiction.”

Color me skeptical, but after checking out their website and contest write-up, I have a hard time seeing Ark Press usher in the next Fitzgerald. They write:

“Ark Press specializes in genre fiction—primarily science fiction and fantasy, but also political thrillers, alternate history, mystery, and historical novels. We focus on stories where humans triumph over adversity—alien, evil, or natural. We promise readers that in every Ark book, ‘The humans win in the end.’

We aim to reclaim the Great American Novel of decades past and serve the reader who thrives on intricate plots, richly imagined worlds, and stories that grapple with the big questions of humanity.”

Who exactly are they looking to pen the next entry into this literary echelon of echelons?

“While the contest is open to anyone, the publisher is reaching out in particular to students in creative writing programs.

‘I feel like there are so many college students out there who would flower artistically where they might not otherwise by having a go at long-form genre storytelling,’ Daniel said.

‘Fiction is the one form of writing that engages the whole mind, the emotions, the spirit, and the intellect,’ he said. ‘Telling and listening to stories is the basic way humans process…well, everything. If you want to be a better communicator, read great fiction.’”

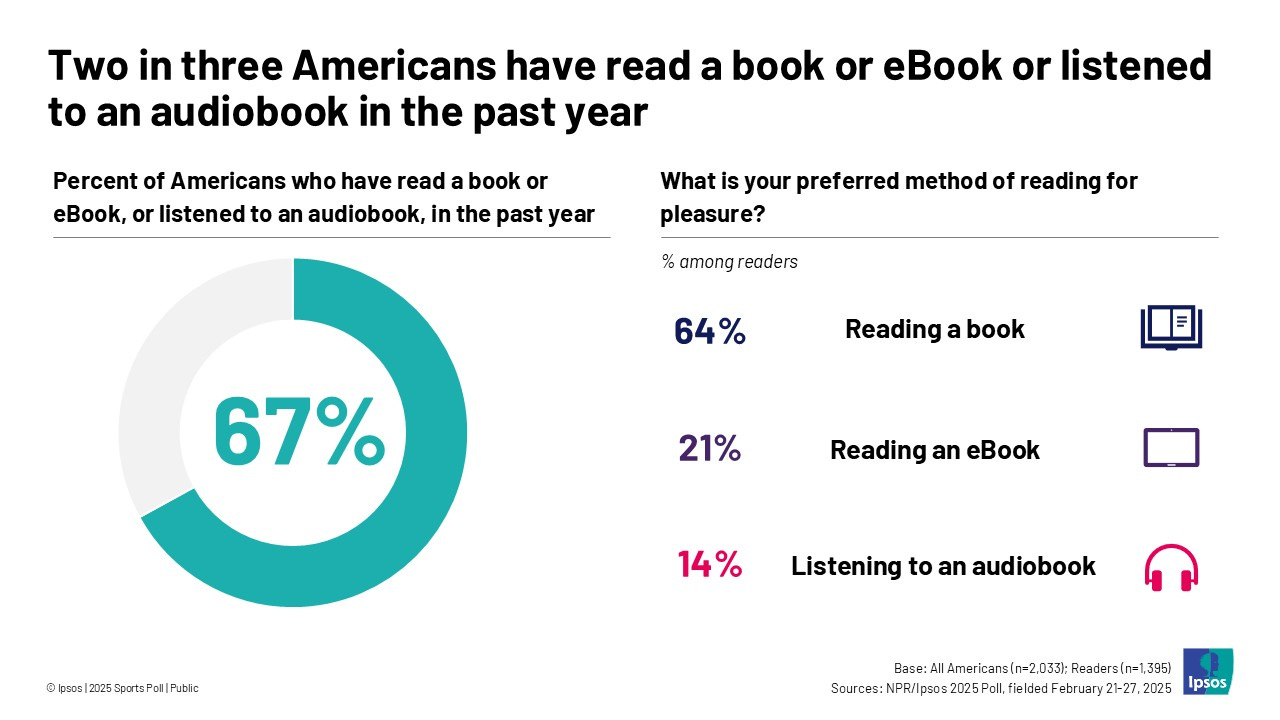

This is where I struggle. If “reading great fiction” is key, what does that mean for this contest? Are college students (or anyone else) reading anymore? This recent Ipsos poll finds a majority hold positive opinions of reading, but many say it is not a priority. For those college students for whom it is a priority, what “great fiction” are they reading (and why is this neither surprising nor encouraging)?

I hope the contest goes well, and I would love to see something truly great come from it. I guess we’ll see. To enter the contest, competitors must submit a complete novel at least 50,000 words long. Submissions are due by Oct. 7.

What’s your favorite Great American Novel (and why)? Leave a comment and let us know.

“Everything became content, then content became nothing.”

—Bruce Eric Kaplan cartoon in The New Yorker (March 31, 2025)

Here’s one attempt from my Headmaster days in support of the “fund students not systems” education model. (You can imagine how well it wasn’t received.)

Goodness is way overated. The Bible tells us so.

After so many years. I finally convinced myself that I can never be good enough to earn salvation and that my only hope is in God's grace.

Yet so many people think that Goodness is the way. People who have been churched for decades. Like me, they aren't listening.

I listen to many teachers. One, I

heard Tim Keller say, "If you think your good deeds are good, they're No Good. If you think they're no good, worthless, etc. then they are good.

A paradox for sure.

Joe

Re: Being a good-ish person, ouch. I just finished reading CS Lewis' The Problem of Pain, and he echoes the Bible's observation on our helpless condition: rebellion is in me, it IS me, and truth be told, I kinda like it, made all the worse by diminishing the extent of its ability to convince me otherwise. It's also why it hurts to surrender and admit I'm in dire need of rescue. Sorry NPR, respect to ya, but I must dissent. Thankful for you brother! :)