Why the Epstein List Matters | What Do We Do with Art Made by Immoral Artists? | Remembrance of Scents Past

Uncovering Hidden and/or Overlooked Realities

Dear Reader,

Sometimes the most important truths are the ones hiding in plain sight.

This week, we look closely at realities we’re too busy—or too comfortable—to confront: the names hidden on the Epstein list and what they might mean for justice; the uncomfortable truths about the artists behind the art we consume; and the overlooked power of smell to connect us to deeper realities and history.

Sources and links for this edition:

#1: Crisis Magazine: Why the Epstein List Matters

#2: The Dispatch: What Do We Do with Art Made by Immoral Artists?

#3: The New Yorker: Remembrance of Scents Past

We live in a world that moves quickly and forgets easily. My hope is that Second Drafts can help us slow down enough to see—and maybe even to smell—what’s true, good, beautiful that’s worth remembering.

Thanks for reading Second Drafts,

Craig

P.S.: If you find these hidden realities worth uncovering, would you forward this issue to a friend who might appreciate a weekly pause for deeper thought? It’s an easy way to help others see—and smell—the world more clearly. Thanks.

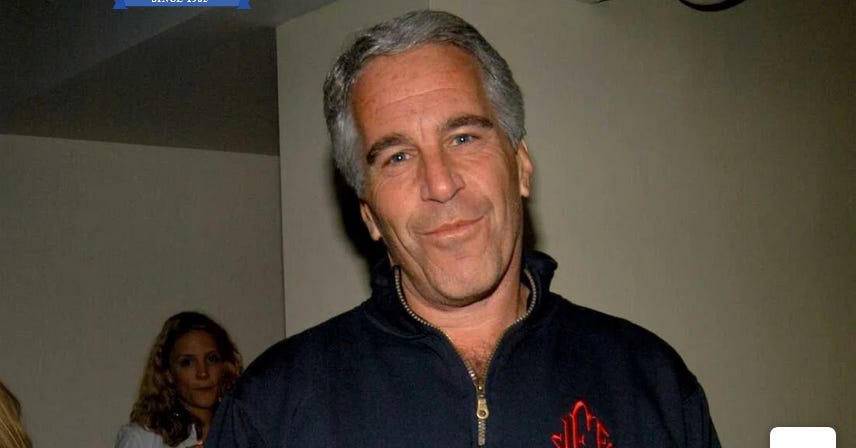

#1: Why the Epstein List Matters

It’s been six years since financier Jeffrey Epstein was arrested for sex-trafficking minors.

Six years. In that time, he supposedly committed suicide, but there was a list of Epstein’s “clients” the Trump administration was supposedly going to release.

But now, according to Attorney General Pam Bondi, that list supposedly doesn’t exist, even though she and dozens others referenced its existence in the past.

As the kids used to say, “I can’t even…”

Crisis Magazine’s editor-in-chief, Eric Sammons, shares my incredulity, writing,

“Since 2019…the story has grown beyond all expectations. A number of major politicians and celebrities have been implicated for allegedly being on the Epstein List, including Prince Andrew and Bill Gates as well as Bill Clinton and Donald Trump. Further, it’s been suggested that Epstein was actually an agent for Israel. Considering the deep connection between America and Israel, and the fact that our connection to Israel has involved us for decades in numerous military conflicts in the Middle East, the idea that we might have blackmailable pedophile government leaders beholden to a foreign government makes this far more than a run-of-the-mill story of political corruption.”

Read that last sentence again. The Epstein List matters for a variety of reasons (sex trafficking and national security being only two). We need Republicans and Democrats to protect Epstein accomplice Ghislaine Maxwell, who has already been convicted but recently said she is willing to testify before Congress. And we need President Trump—who is suddenly and strangely calling for the story to go away since “No one cares”—to stay out of the way. Writes Sammons:

“So what’s going on? Was the whole Epstein case a big nothingburger that got a lot of right-wingers riled up without cause? Or does this mean the Epstein situation is so deeply embedded in our government that Trump and his team are also now beholden to it?

Here’s the truth: I don’t know and you don’t either. But here’s what I suspect: I think either Trump or someone close to him is implicated in the Epstein List, or that someone is implicated who is important to Trump’s goals, and so he decided to try to squash interest in Epstein among his base.”

Whether Trump’s reluctance stems from personal implication or broader political calculation, the fundamental question remains: what exactly would such a list contain that makes it so dangerous to release? One theory I’ve read: the list indeed exists, and is so extensive in its inclusion of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the world that, if made known, the fallout from its publication would paralyze every sector of society across the globe.

Granted, I don’t pretend to know the complexities of releasing such information—the potential legal ramifications, the privacy concerns for anyone falsely implicated, etc. But I’m willing to take that chance. Why? Because doing otherwise would surely be even and eventually worse. As Sammons writes,

“Obviously it’s not good to be lied to and gaslighted by our institutions simply because the truth is superior to a lie, but the constant and bald-faced lies also lead to a total loss of trust in anything someone in authority says. Even when they are telling the truth we suspect they are lying, and a society simply cannot function like this for long. Sadly, the most likely path becomes revolution, which is often violent in nature.”

We may never get the full truth, but we can demand transparency from those in power, refusing to let this be memory-holed under the weight of politics, celebrity, and collective apathy.

The Epstein list matters because people matter—and the image of God in those trafficked and abused demands our outrage and our action. If the truth is too explosive to reveal, that tells us everything we need to know about how deep the corruption runs. And yet, even now, there is time to choose truth, to protect the innocent, to punish the guilty, and to reform what is broken before it breaks us.

But that window is closing.

#2: What Do We Do With Art Made by Immoral Artists?

My friend Karen Swallow Prior is the queen of asking questions all people—especially Christians—need to consider. In her most recent essay in The Dispatch (access through creating a free account), Prior unleashes her question cannon:

“How much can we separate art from the artist? Can we value art created by artists who live deeply immoral lives or hold objectionable views? Can we enjoy art when we learn the artist has harmed others through the process of making his art? Should we?”

Her inquiries are as evergreen as they are timely. While considering historical writers like the Marquis de Sade, John Milton, Charles Dickens, George Eliot (who was actually Mary Anne Evans), and Flannery O’Connor, Prior also writes about filmmaker Roman Polanski and other examples from today’s headlines:

“Superficial, merely political responses to such questions abound on both the left and right. Many among the generation that grew up reading Harry Potter books, for example, no longer want anything to do with the work of the series’ author, J.K. Rowling, because of her public stances against transgender ideology. On the other side of the political spectrum, the U.S. Naval Academy removed hundreds of titles from its library shelves this spring during a purge of DEI influences (but returned many of them following a public outcry).

But knee-jerk censoriousness rooted in politics is not the same as honest grappling by the thoughtful reader, viewer, or listener. Every conscientious person must consider these kinds of questions at some point.”

To do that well, we need help from outside our own preferences and opinions.

“Our tastes are formed by experience, learning, and community—and for the Christian that includes the community of the church, which has a role (whether intentionally embraced or not) in shaping our tastes and forming our standards…

…But the church community plays a much bigger role in forming our tastes and cultivating the art we consume than many of us think. I’m referring to the role played by the publishing, music, and celebrity industries that create and promote the art and artists filling our churches, bookstores, streaming services, and podcasts. At its best, this is just Christian capitalism doing what it does. But its more sinister side appeared—once again—with recent news about longtime Christian music artist Michael Tait, who has been credibly accused by multiple victims of sexual assault, unwanted sexual advances, and drug abuse. And all this was considered for years the “worst kept secret” in the business, a secret apparently kept by countless people inside (and outside) the Christian music industry who directly or indirectly benefited from Tait’s commercial success.

What do you do when an artist who has acquired fame and fortune proclaiming one set of beliefs and values lives a double life rooted in the opposite? It seems to me that such art loses its savor and is something to spit out rather than enjoy.”

I experienced such savor-losing concerning formerly Christian artist Derek Webb. For those not familiar, Webb got his start playing guitar for the band Caedmon’s Call back in the ‘90s before launching out on his own with two records that positively piqued my interest in Reformed theology (She Must and Shall Go Free, 2003) and challenged my thinking on what often passes for evangelical Christian ethics (Mockingbird, 2005). I was very thankful for his vocation and voice.

However, after his extramarital affair and subsequent 2014 divorce from Christian singer-songwriter, Sandra McCracken, my interest in Webb’s songwriting waned. I followed from a distance his deconversion, and his sad “one man’s apostasy is another man’s liberty” declaration on X. His 2023 album, The Jesus Hypothesis, chronicled aspects of his rejection of faith and featured the blasphemous song, “God in Drag,” and the equally disturbing song (and video), “Boys Will Be Girls.”

After reading Prior’s article, I got to thinking about Webb and listened for the first time to his 2025 album, Survival Songs, a record that Good Faith Media called “a love letter to the LGBTQ+ community” with titles like “Queer Kid” and “Sola Translove.” The album fulfills Webb’s attempt at commiseration with the gay and trans communities, but is little more than emotional coddling, unlike the hard-hitting song of conviction, “Wedding Dress,” which Christian radio stations hesitated playing due to vivid biblical language.

Ironically, “Wedding Dress” is still—somehow—Webb’s #1 song on Spotify.

Whether it be Webb, Michael Tait, or other “Christian celebrities” (an oxymoron if there ever was one) like Chip and Joanna Gaines who claim faith in Christ and then act against it, Prior’s conclusion is apropos on many levels:

“When an artist produces work rooted in his or her professed faith and is supported by that faith community and then betrays those beliefs, more issues come into play than simply the objective quality of the work. The spiritual condition of the artist matters. The welfare of victims matters. The systems and structures that supported the artist are implicated if those systems and structures enabled or covered up wrongdoing. What do we do when works of art and the artists who create them destroy the very things they claim to profess and express?

I think that as far as it depends on us, we seek art elsewhere. And we take our time, attention, and dollars with us. The question isn’t merely about separating the art from the artist. It’s also about separating ourselves from works that are not good, true, and beautiful.”

In application, I’ll still listen to Webb’s initial albums and appreciate them for what they were. But I’ll do so from previously-purchased CDs, not Spotify.

We can all be prone to love art more than truth, to elevate artists beyond accountability, to celebrate work built only on brokenness rather than the pursuit of redemption and the eventual restoration of it. But as we consider what art we consume—and what artists we platform—I agree with Prior: we need courage to choose what is true, good, and beautiful, and to walk away from what is not, taking our time, attention, and dollars with us.

#3: Remembrance of Scents Past

Living in the heart of the Midwest, I’m probably the last guy you’d expect to be an actual subscriber to The New Yorker. After snagging a killer deal, my subscribing is an intentional attempt to read beyond my Midwest mindset the stuff the more so-called “elite” in our society might spend time reading.

This recent feature article, for instance, about smells created by scent designers is the most recent one that caught my nose:

“This past August, in a windowless room of the British Library, in London, Tasha Marks was enacting her own form of time travel. Marks is a scent designer who works with museums, heritage sites, and other cultural spaces to create odors that can open an instant portal to the past. The library had commissioned her to concoct historical smells for an exhibition about the lives of medieval women. On a conference table, Marks placed an array of bottles and fanned out several mouillettes—the paper strips that perfumers use to sample fragrances.

The library would be putting on display a thirteenth-century edition of a remarkable Latin manuscript called ‘De Ornatu Mulierum,’ a compendium of beauty and hygiene advice for women. Marks had obtained ingredients listed in the manuscript to re-create the smell of a breath freshener and of a hair perfume that would have been applied as a powder, like dry shampoo. (‘Let her make furrows in her hair and sprinkle on the aforementioned powder, and it will smell marvellously.’) The text didn’t offer exact recipes—no proportions were provided—so there was an element of improvisation, allowing Marks to act as both historian and artist.”

But historical scent designing apparently requires more than just improvisation.

“The show, ‘Medieval Women: In Their Own Words,’ would also feature some scents that were imaginative leaps. One of these would evoke a vivid mystical vision of the religious figure Julian of Norwich in which she was nearly smothered by the Devil in a vile ‘stinke.’ Marks told the library staff that she’d made a concoction, foregrounding artificial approximations of scorched excrement, that was ‘smoky and fetid and bodily’ but ‘not sick-making.’”

Artificial approximations of scorched excrement? If we still raised hogs, I could have provided an unlimited amount of the real thing (scorching being extra) at half the price. But not all historians have picked up on the scent of scent design:

“Some scholars find efforts to mimic historical smells a little too consumer-driven and theme-parky. Mark M. Smith, a professor of history at the University of South Carolina, is the author of ‘A Sensory History Manifesto,’ in which he notes that ‘curatorial tricks’ aiming to re-create historical sensations can be misleading. Although it might be ‘theoretically possible to re-create,’ say, the smell of a medieval dungeon or a nineteenth-century tenement house, Smith [said] in an e-mail, ‘it is impossible to consume, to experience those sensations the same way’ that people did at the time. Something that smells putrid to us now, for instance, might not have assaulted medieval noses in the same way.”

Despite critics, it’s not only museums jumping on the scent bandwagon:

“A recent Broadway revival of Thornton Wilder’s ‘Our Town’ had a minimalist set, but, at key moments, scents were dispersed into the theatre to establish a nostalgic mood—heliotrope, vanilla ice cream, frying bacon. For the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute show in 2024, a smell artist named Sissel Tolaas analyzed molecules extracted from the clothes and accessories on display in order to re-create how they had smelled on their original wearers. A reporter who visited the show for NPR said, ‘What I am smelling is the scent of a woman’s skin taken from the dress she wore around the turn of the last century. This is a completely different way of experiencing an object at a museum. Smell makes the women who wore these dresses feel present.’”

Beyond the novelty factor, the science of association is what’s truly fascinating:

“There are physiological reasons why smell can trigger memories more effectively than other senses. The olfactory cortex is closely connected to the amygdala, a part of the brain that processes emotions, and to the hippocampus, a key region for memory. Rachel Herz, a neuroscientist at Brown University who studies smell, told me that it is the only sensory system in which a sensation is produced and consciously experienced in the same regions of the brain where emotions and memories are made. ‘This uniquely direct neuroanatomical link,’ Herz has written, helps explain why ‘odor-evoked memories’ can be so emotionally potent. The flood of memories unleashed by Proust’s madeleine was as much a function of smell as of taste. Marks noted to me that, when we recall things we’ve seen or heard, we are always remembering the most recent time we remembered it, as well, and so the initial impression ‘dilutes over time—whereas with smell and taste it’s the same primal stimulus again.’ Sniffing something that you haven’t encountered in twenty or thirty years—Play-Doh, fresh-cut hay, your grandmother’s laundry detergent—can be as vivid a sensory experience as it was the first time, while also being almost psychedelically nostalgic.”

While it’s easy to dismiss all this as another weird elite hobby, there’s no denying that scents do something screens can’t: they pull us into the past with startling immediacy. Eye-rolling aside, maybe it’s worth appreciating that there are still people trying to help us experience history—and the world around us—with our senses. Whether the smell of medieval hair powder or frying bacon on Broadway, scent design is a reminder that life isn’t just something to watch, but to live.

And that, to me, smells like something worth remembering.

“The world is full of magical things patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.” W.B. Yeats

I’m a little worried about the world when we are agreeing on so many issues!

Something about this concept of scent recreation stinks